Administration of Maternal Vaccinations

Safer Culture » Lessons Learned »

Administration of Maternal Vaccinations

Emerging evidence of a quality metric in obstetric care

Background

Immunization against vaccine-preventable diseases is an essential, recommended component of women’s primary and preventive health care. Despite clear guidance from public health agencies, maternal vaccination rates lag behind national goals. At the beginning of the project only ~44% of women admitted to Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital (CMHH) were vaccinated against pertussis prior to delivery.

Our project has focused on 3 primary areas:

- Accurate linkage of data from new Tdap screening tool to report

- Development of a dashboard to display Tdap screening tool reports

- Further analysis of the maternal survey.

Lessons learned at Memorial Hermann Healthcare System

Looking at the each of the Safer Culture enabling factors, we identified and learned from the following gaps, barriers and/or facilitators that have led to both success and failure:

- Organizational Enabling factors

- Leader commitment & prioritization of safety

There is high leadership commitment to vaccinations delivery across the hospital system. - Policies and resources for safety

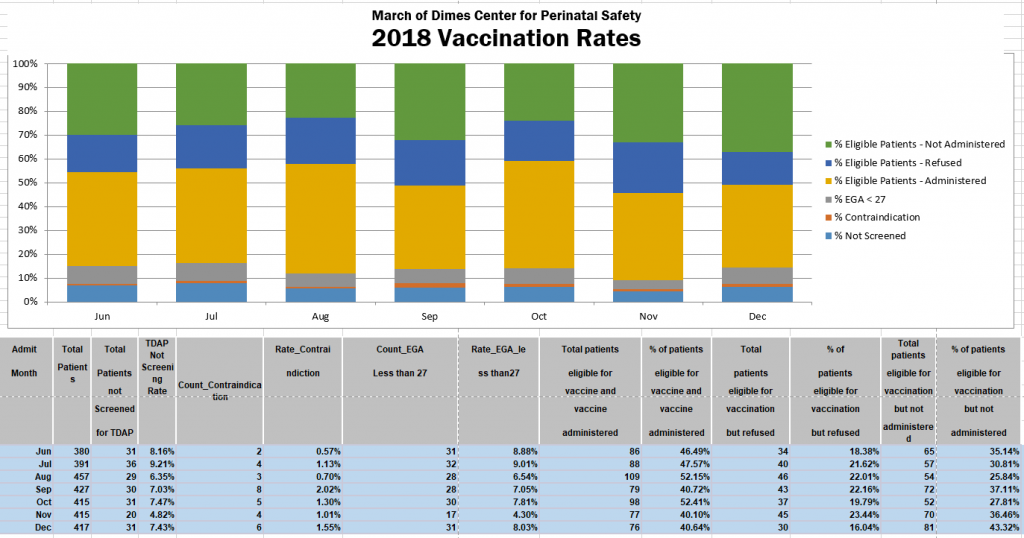

Policies for implementing effective vaccination screening and delivery; however, they are variable within the institution (e.g., CMMH antepartum vs CMMH postpartum units) and by vaccine (Tdap vs influenza vaccine). At this time, screening for influenza vaccine status is mandated. Therefore, there is greater organizational monitoring and accountability for influenza screening rates as manifested by daily monitoring, reporting, and assessment of influenza vaccine screening fall-outs. In contrast, Tdap vaccine screening is not mandated and reflects a lower accountability at an organizational level. The organization supported updating the Tdap vaccine screening form to reflect national guidelines, but doing so was not a MHHS priority, as the update process lasted nearly a year. It has also taken close to a year to develop tools to accurately monitor Tdap vaccine screening and delivery based on the updated screening form. We met with the MHHS IT analytics team in May 2018 to discuss our requirements to automate the maternal immunization vaccination report and dashboard, based on the new Tdap vaccine screening form. Throughout June and July 2018, we had multiple meetings with the MHHS IT analytics team to discuss and clarify requirements for the maternal vaccination report and dashboard.Although a draft of the report was initially developed in mid-August 2018, technical errors were discovered immediately. Throughout August and September 2018, there were multiple conference calls with the MHHS IT analytics team to troubleshoot and fix those technical errors. This took longer than anticipated due to analyst’s other work-related commitments. Finally, in October 2018, it was decided to split up the maternal vaccination report automation from the dashboard development so two analysts could be engaged, which would speed up the project. However, due to resourcing issues, by January 2019, a second analyst from MHHS IT was still not engaged.With a second analyst on-boarded in mid-January 2019, the work on report automation finally began. Following the report development, throughout February and March 2019, there were several rounds of data validation, which found discrepancies between the Tdap screening data of patients seen at UT Physicians and other private providers, due to mismatching in the patient’s medical records. A follow-up with the MHHS IT analytics team found that the process that maps the medical record number (MRN) of patients from UT Physicians and other private providers to the MHHS MRN had been put on hold. The MHHS IT interface team and analytic team developed a plan to update/map the MRNs from UT and private providers with MHHS MRNs. We are still waiting for the IT interface team to complete this updating/mapping so we can resume validating the automated maternal vaccination report data. In the meantime, we attempted to create our first Tdap dashboard as shown in the figure below.

- Leader commitment & prioritization of safety

In February 2018, MMHS incorporated vaccination status into their newly implemented Mother Baby Unit (MBU) Multidisciplinary Discharge Rounds (MDDR), a program designed to improve communication and eliminate barriers of patient throughput through the Obstetric Service Line. MDDR are part of a larger system effort to implement OB Milestone Clinical Pathways that focus on clinical efficiency with tasks assigned on a timeline.

For example, vaccination screening not completed by 6 hours from admission would result in immediate action. Patients refusing vaccination are to be identified and follow-up rounding added to the action board for the charge nurse or manager to be completed by 4pm daily. After issues of non-compliance of utilization of the OB Milestone Pathway were identified (e.g., vaccination status not always reviewed), we implemented a pilot using an MDDR coordinator in June 2018. This role solely focused on completing the pathway and addressed any barriers or missed tasks by nursing. Analysis of the intervention is in progress.

- Group Enabling Factors

- Cohesion

Within UT and MH, there are several groups to consider: Outpatient OB (UT, MHMG and other private physician groups) practices that refer patients for delivery as well as groups within MH-TMC (postpartum and antepartum). These OB practices vary in how they screen and deliver vaccines and then report information to MH-TMC at the time of delivery (see prior progress report). Ideally, practices forward vaccine status information similarly to prenatal labs. Additional groups include those within Memorial Hermann (postpartum and antepartum unit). At the time we updated our Tdap screening form, we opted (with input from stakeholders) to expand screening to include both Antepartum and Labor and Delivery nurses (i.e., screening form could be started by antepartum / L&D nurse and then completed by postpartum nurse with any needed vaccine given by postpartum nurse). Prior to this change, only postpartum nurses were screening. This change has resulted (at least anecdotally) in confusion among nurses as to: 1) who is responsible for screening, and 2) postpartum nurses no longer completing the form. Ownership of the process also has been variable due to OB nurse manager staff turnover. We are currently reaching out to nurse managers to obtain input in how to address this variability in screening. - Psychological safety

Individual physicians and nurses have had contradicting beliefs about the administration of vaccinations, with less than full acceptance of the need for Tdap and influenza vaccination during pregnancy and postpartum. However, the issue has been openly discussed and personal beliefs have not influenced patients being offered and receiving the vaccinations.

- Cohesion

- Individual Enabling Factors

- Safety knowledge & skills

Several individuals are important to consider in vaccine screening and delivery (providers, nurses and patients). Most physicians endorse antenatal Tdap vaccination, but not all of their clinics can provide the vaccine. Those that do not provide the vaccine in their offices refer the patients to other venues (e.g. Walgreens). Among OB nurses at MH-TMC, there was task delineation confusion about the Tdap vaccine with the assessment process change. We attempted to address this by updating our Tdap vaccine screening form to more clearly delineate recommendations depending on whether patient was antepartum or postpartum in 2018. Reeducation on the vaccination process has occurred. Our survey of postpartum mothers provided some insight into their knowledge. The majority of postpartum women spoke English [153 (79.8%)] and had received prenatal care [185 (95.9%)], and 121 (62.7%) reported having received the Tdap vaccination at their OB’s office [80 (66.6%0]. Among women not vaccinated [65 (65.3%)], common reasons included “healthcare provider did not recommend” or “did not know I needed.” Thirty (15.0%) EHR vaccination screening forms did not match our survey results (e.g. form stated mother vaccinated when was not or vice versa). We conducted inferential data analysis of the surveys we collected and found no significant difference between patients receiving Tdap vaccine at their OB office prior to admission at CMMH vs following admission to CMMH. We also stratified the data based on the provider’s practice type (i.e. UT and non-UT(private)) and also did not find any significant difference in the Tdap vaccination rate. In November 2017, we presented to the Perinatal Parent Family Advisory Council, which gave us insight into parent’s knowledge about vaccines. Parents were very receptive to information about vaccinations and expressed support to more education about vaccines during pregnancy. They appreciated details regarding infections among pregnant women, dynamics of immunologic response to vaccine, and transplacental transfer of immunoglobulin. - Sense of control

We have not directly assessed sense of control among individuals (providers, nurses and patients); however, there remains a conviction among many of the nurses that they are contributing to the safety of the newborn by vaccinating the mother. Currently, ~ 10% of pregnant women are not getting screened for Tdap vaccine status during their admission. This could reflect the assessment process change (now being done in L&D vs Postpartum) or it could reflect a low sense of control among some OB nurses. Similarly, patients presenting to CMHH not having received Tdap vaccination (48.5%) could reflect a low sense of control among OB providers.

- Safety knowledge & skills

Individual commitment & prioritization of safety

Individual commitment and prioritization of safety varies by provider, with some having more than others. Physicians and nurses are committed to safe vaccination practices to protect mother and baby.