Alcohol Withdrawal Prevention & Treatment

Original Date: 06/2022

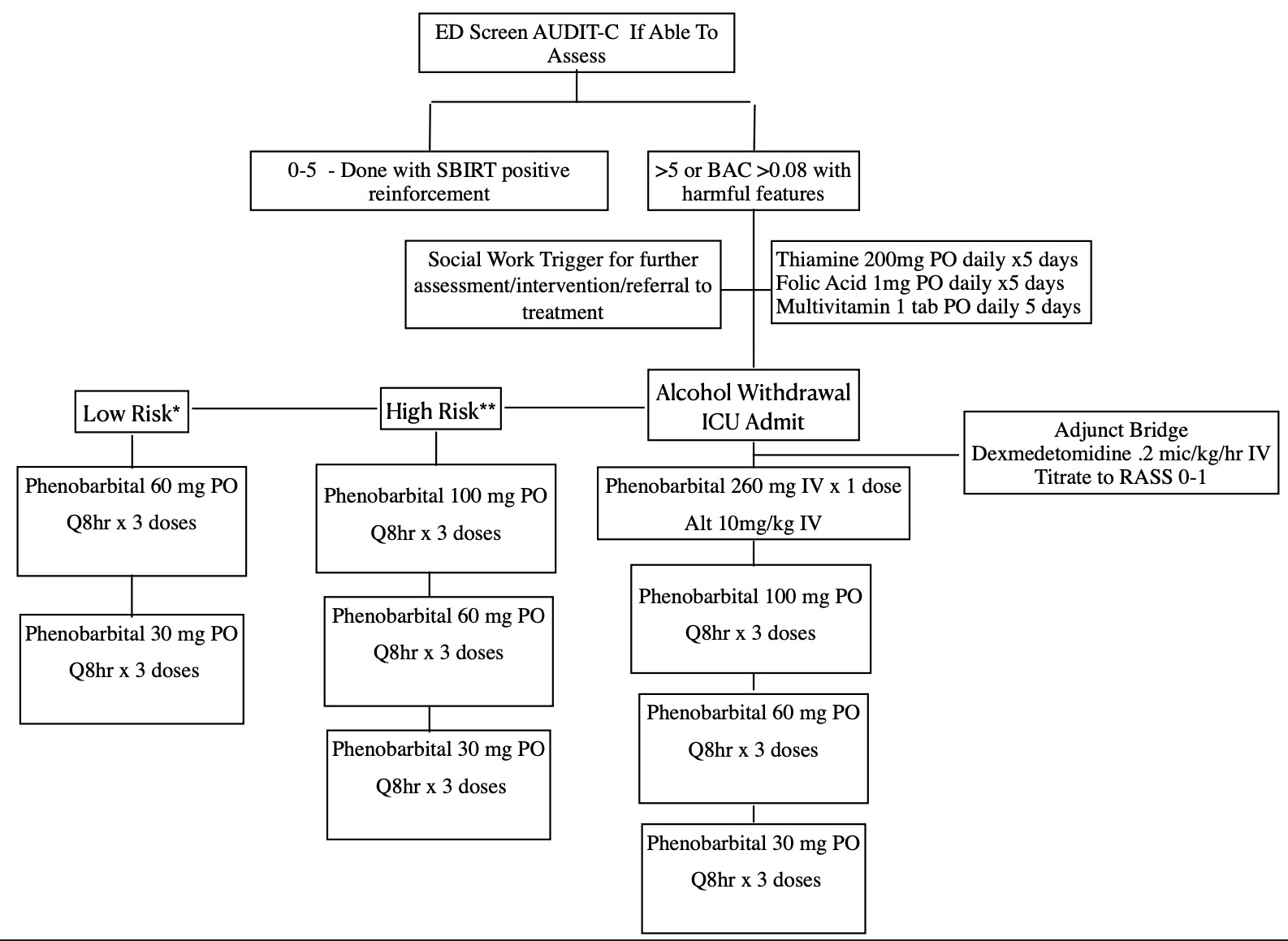

Primary Mono-Therapy Route:

- For intubated patients, receiving a Propofol or midazolam infusion, no additional therapy required while on infusion.

- Excluded: Those on essential medications or conditions that interact with phenobarbital. Advanced cirrhosis with hepatic encephalopathy (MELD >10), antiretroviral treatment, chronic use of phenobarbital.

- If agitation/delirium persists after a total cumulative phenobarbital dose of 20 mg/kg, do not increase dosage consider different diagnosis.

- For breakthrough symptoms, give phenobarbital 100-200mg PO q6-8hr to a target RASS of -1 to 0.

- If a patient develops active delirium tremens after starting the phenobarbital taper, transition to the beginning of the “Active Delirium Tremens” pathway.

Harmful Features

*History of heavy alcohol use (>8 drinks a week for women or >15 drinks a week for men)

*Alcohol abuse with active signs/symptoms of withdrawal not meeting high risk criteria

**History of alcohol withdrawal seizures OR history of DTs

Diagnosis DSM V:

- History of ETOH – The most important component of the diagnosis.

- Charts may list “alcoholism” as a current problem despite cessation – verify accuracy

- Reduction in alcohol use that has been heavy and prolonged. History of withdrawal when they stop drinking?

- Based on conditional recommendations: ED or hospital-based screening with brief intervention and referral to treatment for appropriate patients in order to reduce alcohol-related injury. (SBIRT)

- In ED or on tertiary exam perform: AUDIT questionnaires. If high risk consult social services or case management for alcohol prevention programs.

Timing:

- ETOH withdrawal seizures usually occur within hours and 1-2 days of ETOH cessation.

- Delirium tremens usually occurs 2-4 days after ETOH cessation

- Delirium starting hospital day >4 days is more likely another etiology.

Signs and Symptoms of Alcohol Withdrawal DSM V:

- Autonomic hyperactivity – Agitated delirium with hypertension, tachycardia, and diaphoresis

- Transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucinations

- Anxiety

- Insomnia

- Psychomotor agitation

- Nausea and Vomiting

- Increased hand tremor

- Generalized tonic – clonic seizures

- Delirium tremens is a diagnosis of exclusion. Therefore, consider other causes of delirium

- Findings suggestive of alternative diagnosis: somnolent following moderate to low dose benzodiazepines. Agitation despite >15mg/kg phenobarbital. Delirium without other features of delirium tremens (absence of hypertension, tremors, etc.)

Treatment:

- Supportive Care

- Electrolyte Repletion: Patients are deficient in multiple electrolytes: K, Mg, and Phos

- Severe ETOH causes decreased total body Mg. 4mg IV q12hr MgSO4 recheck Mg level 24-48 hours

- Total body magnesium will take 2-3 days to equilibrate

- Severe ETOH is high risk for refeeding syndrome and may require Phos repletion. Start nutrition gradually and monitor electrolytes closely.

- Severe ETOH causes decreased total body Mg. 4mg IV q12hr MgSO4 recheck Mg level 24-48 hours

- Monitor Glucose q4 hours. NPO patients with ETOH liver disease or cirrhosis may have impaired glycogen reserves and are at high risk for hypoglycemia.

- Thiamine – High risk for Wernicke’s encephalopathy, which mimics ETOH withdrawal.

- Administer thiamine 200mg PO Daily

- Consider B6 Pyridoxine therapy for ETOH related seizures: 25mg PO q24 hours

- Consider B12 and Folate for macrocytosis: 1000ug B12 & 1mg Folate PO q24 hours

- Electrolyte Repletion: Patients are deficient in multiple electrolytes: K, Mg, and Phos

Phenobarbital

- In severe ETOH withdrawal phenobarbital has uniform efficacy where benzodiazepines fail to work

- No paradoxical reactions and less delirium compared to benzodiazepine

- Predictable pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Greater therapeutic index. Ease in following serum levels

- Therapeutic doses: 5-25mg/kg IBW to achieve serum level of 10-40ug/mL.

- Toxic dose: (stupor/coma) >40mg/kg IBW to achieve serum level of >64ug/mL

- Prolonged half-life of 3-4 days allows precise dose titration and gentle auto-taper once therapeutic level achieved.

- Excellent anti-epileptic activity, can be administered by all routes, and little sedation at moderate doses. Allowing for use prophylactically where withdrawal is expected.

- Contraindication:

- Allergy, diagnosis of ETOH withdrawal unclear, and advanced cirrhosis with hepatic encephalopathy, Drug interaction with HIV treatment

- Caution – patients who have received previous doses of benzodiazepine, phenobarbital will act synergistically, therefore need to start at low dose. Caution with patients taking medications to suppress respiration (opioids)

Treatment

- Load at 260mgIV or 10mg/kg IV to start. This will give a serum level of 15ug/ml. Reduce the need for ICU admission.

- Titration – 100-200mg PO q 8hr to a target RASS 0-1.

- Limit cumulative dose to 20-30mg/kg ideal body weight. Consider symptoms unrelated to ETOH withdrawal if at 30mg/kg. Addition of antipsychotics and alpha agonist need to be considered.

Useful Links:

- AUDIT-C: https://www.mdcalc.com/audit-c-alcohol-use

- Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Scale: https://www.mdcalc.com/prediction-alcohol-withdrawal-severity-scale

Continued Education:

Benzodiazepine

- Mild – Moderate symptoms

- Some do not respond, therefore consider phenobarbital

- Diazepam – Dosed with escalating doses as needed q5-10min IV.

- PO 10mg q6hr

- IV 10mg q5-10min (10mg, 10mg, 20mg, 20mg, 20mg, 40mg, 40mg, 40mg, 40mg)

Ketamine

- Rarely, a dissociative dose of ketamine (e.g. 1.5-2 mg/kg) may be useful for a patient with alcohol withdrawal who is profoundly and dangerously agitated.

- Dissociative ketamine will achieve behavioral control for approximately 30 minutes. This is enough time to administer phenobarbital (e.g. 5-10 mg/kg).

- As the patient is waking up from the ketamine, phenobarbital may be used to prevent re-emergence.

- Phenobarbital is used here in a fashion similar to a benzodiazepine to prevent re-emergent agitation.

- Dissociative ketamine (like dexmedetomidine) isn’t a destination therapy – this simply buys time to facilitate transition to phenobarbital.

- Pain-dose ketamine – untreated pain can be difficult for patients with alcohol withdrawal. Pain can be a driver of agitation, which may potentially lead to excessive use of sedatives.

Dexmedetomidine

- Achieve behavioral control while you’re working on gradual up-titration of phenobarbital or performing other tests

- Patient has already received a moderate amount of phenobarbital (e.g. >10-15 mg/kg) and is getting increasingly agitated overnight. Dexmedetomidine is an excellent drug for nocturnal delirium, so this can decrease insomnia. Stop the dexmedetomidine the next morning and re-assess whether more phenobarbital is required. A patient who is suffering from nocturnal agitation (rather than alcohol withdrawal) may be perfectly fine the next morning with the dexmedetomidine discontinued – without requiring additional phenobarbital.

- Treatment of non-alcohol-related delirium

- Dexmedetomidine is never a destination – it’s a short-term bridge to control symptoms while the situation clarifies itself. Does not protect against seizure and should never be used as a sole agent for DT

Antipsychotics and Clonidine

- They do not treat underlying problem (inadequate GABA signaling and excessive glutamate activity). They do not have anti-epileptic activity, and they can mask symptoms of withdrawal.

- Some patients will develop a nonspecific, mixed delirium state following treatment for alcohol withdrawal. None alcohol related delirium (NARD).

- Antipsychotics (preferably small doses of PRN IV haloperidol) and oral alpha-agonists (e.g. clonidine) may be helpful for symptomatic therapy of NARD.

- Use the smallest possible dose to achieve symptomatic control.

- Clonidine .1mg po q4hr, can increase up to .4mg q4hr.

- Propranolol 10mg PO q6hr

- Haloperidol 2.5-5mg IV q1hr may titrate to cumulative dose 10-20mg

- Ziprasidone 10mg PO q12 hr

- Risperidone .5mg PO q12hr

- Olanzapine 5mg IM/IV QHS (5-20mg QHS in ventilated patients)

- Quetiapine 50mg PO q12 hrs and up-titrate. Do not go higher then 200mg BID. Consider higher PM does then AM does to promote sleep/wake cycle

Background:

Alcohol abuse is a global health problem, ranking seventh among the leading causes of death and disability. 2 to 7% of patients with heavy alcohol use admitted for general medical care develop severe AWS. Symptoms of AWS occur because alcohol is a central nervous system (CNS) depressant. AWS is a fatal medical condition characterized by an imbalance between inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) and excitatory neurotransmitter NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor stimulation secondary to chronic ethanol intake.

Mild withdrawal symptoms like insomnia, tremulousness, mild anxiety, gastrointestinal upset, anorexia, headache, diaphoresis and palpitations are due to CNS hyperactivity. They usually appear within 6 hours of the last alcoholic drink. Alcohol withdrawal seizures usually occur within 12 to 48 hours after the last drink predominantly in patients with a long history of chronic alcoholism. Such seizures left untreated may develop delirium tremens (DT). Thus, AWS ranges from mild to severe symptoms that can lead to fatal DT requiring ICU admission and incurring high health care cost. Severe AWS is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate from severe AWS is as high as 20% if untreated. Early recognition and improved treatment can reduce the mortality rate about 1-5%.

AWS is usually managed with standardized administration of benzodiazepines, supportive care, and continuous evaluation using a validated clinical scale such as the revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment of Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). This protocol of CIWA-Ar–based administration of benzodiazepines has many imperfections. It puts a heavy burden on the nursing staff, as it requires very frequent monitoring of the patients.

Severe AWS accounts for only 10% of the roughly 500,000 annual cases of AWS episodes that require pharmacologic treatment. Treatment is typically centered on supportive care and symptom-triggered benzodiazepines. But some of this subset of patients are refractory to benzodiazepines, defined as >10 mg lorazepam equivalents in 1 hour or >40 mg lorazepam equivalents in 4 hours. Doses exceeding this threshold provide little benefit and put patients at risk for increase morbidity and mortality, over sedation, ICU delirium, respiratory depression and hyperosmolar metabolic acidosis and death. Many clinicians feel uneasy giving escalating doses of diazepam (starting from 5 mg and rising to 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg, and even 80 mg per dose) every 5 minutes. The patients often get under-dosed, develop DT and require intubation for airway protection. Large cumulative doses of lorazepam may develop both delirium and respiratory depression

References:

Alonzo, Anika, et al. “The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management.” American Society of Addiction Medicine, 23 Jan. 2020.

Ammar, M. a., Ammar, A. A., Kassab, H., Becher, R., & Rosen, J. (2020). Phenobarbital Monotherapy for the Management of Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome in Surgical Trauma Patients. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 55(3), 294-302.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Fourth Edition (DSM-V)

Farkas, J. (2016). Internet Book of Critical Care. N.p.: EMCrit Project. Retrieved from https://emcrit.org/ibcc/etoh/#top

Kodadek, L. M., Freeman, J. K., Tiwary, D., Drake, M., Schroeder, M., Dultz, L., … Rattan, R. (2019). Alcohol-related trauma reinjury prevention with hospital-based screening in adult population: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma evidence-based systematic review. Journal of Trauma Acute Care Surgery, 88(1).

Nisavic MD, Nejad SH, Isenberg BM, et al. Use of phenobarbital in alcohol withdrawal management – A retrospective comparison study of phenobarbital and benzodiazepines for acute alcohol withdrawal management in general medical patients. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(5):458-467.

Oks M, Cleven KL, Healy L, et al. The safety and utility of phenobarbital use for the treatment of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the medical intensive care unit. J Int Care Med. June 2018, doi: 10.1177/0885066618783947.

Schmidt KJ, Doshi, MR, Holzhausen JM, et al. Treatment of Severe Alcohol Withdrawal. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2016; 50(5):389 –401.

Tidwell WP, Thomas TL, Pouliot JD, et. al. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome: phenobarbital vs CIWA-AR protocol. Am J Crit Care 2018;27(6):454-460.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center Division of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care. (2016). Alcohol Withdrawal. In Trauma Substance Abuse Guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.vumc.org/trauma-and-scc/sites/default/files/public_files/Protocols/TICU%20Substance%20Abuse%20PMG.pdf