Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta

Original Date: 04/2003 | Supersedes: 07/2017 | Last Review Date: 10/2025

Purpose: To outline use of REBOA in cases of life-threatening non-compressible torso hemorrhage (trauma and obstetric).

Recommendations:

- REBOA may be considered as an adjunct to temporary hemorrhage control in patients with life-threatening non-compressible torso hemorrhage arising below the diaphragm, including instances of obstetrical hemorrhage, including placenta accrete spectrum (PAS).

- REBOA should not be used in:

- Patients where source(s) of bleeding arises cephalad to the diaphragm.

- Penetrating thoracic trauma with:

- Clinically significant hemothorax

- Possible or confirmed cardiac injury

- Possible or confirmed thoracic vascular injury

- When the need for REBOA is anticipated, a common femoral arterial line should be placed immediately.

- REBOA may be considered in non-trauma patients, at the discretion of Trauma Surgery staff.

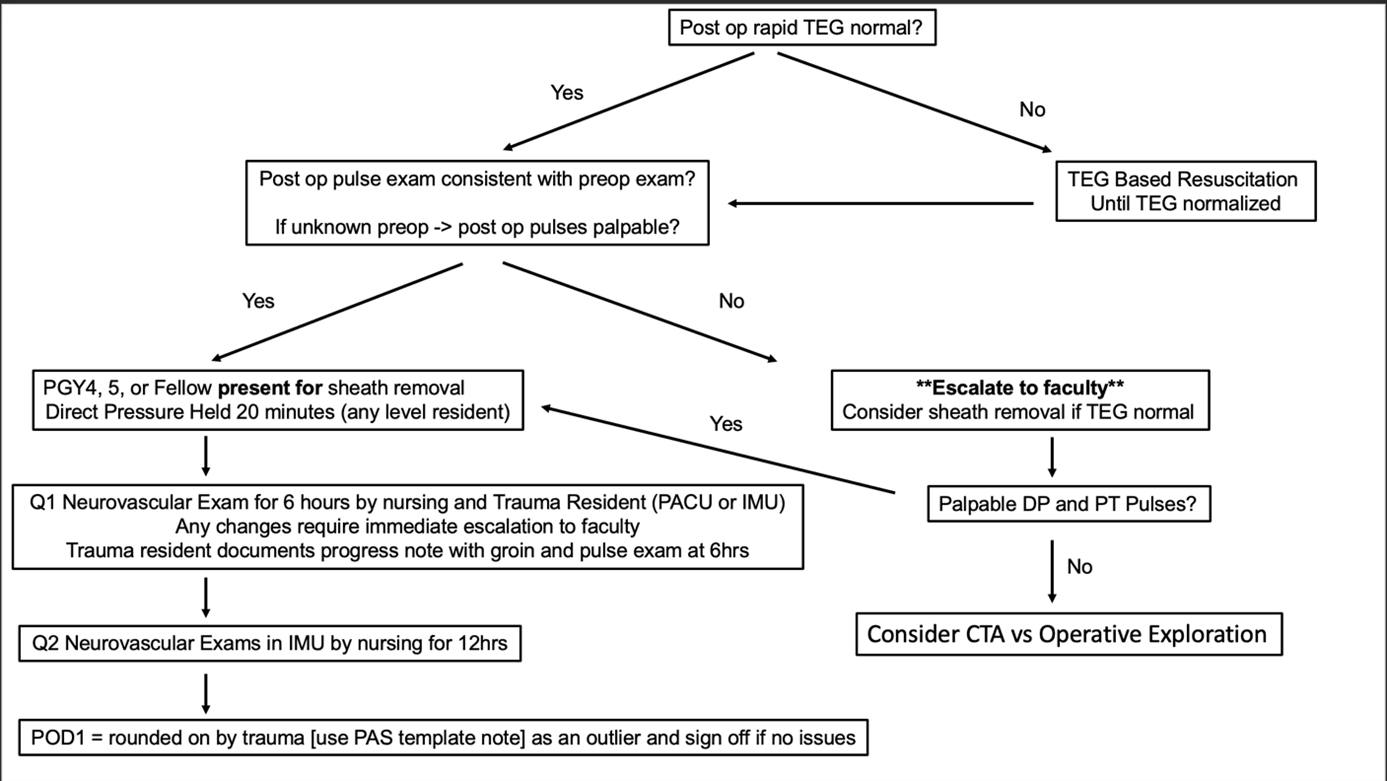

- Once the patient has been stabilized and REBOA is no longer necessary:

- Remove the REBOA catheter completely and flush the femoral artery introducer sheath with normal saline (may be used temporarily for arterial blood pressure monitoring).

- Confirm pedal blood flow by palpation or Doppler.

- Remove the femoral artery introducer sheath as soon as possible after obtaining a normal rapid TEG.

- Once removed, the following steps should be taken:

- Apply manual compression for 30 minutes or repair the femoral artery primarily.

- The patient should remain supine (no hip/knee flexion) for 6 hours.

- A duplex arterial ultrasound of the access site should be obtained 48 hours after sheath removal to assess for pseudoaneurysm or thrombus formation.

Summary:

- A single randomized controlled trial of REBOA vs no REBOA has been published. The UK REBOA study suggested that REBOA plus standard care may be harmful in trauma patients. However the study’s limitations may limit its generalizability, especially in high volume trauma centers where REBOA is routinely utilized.

- The current literature base continues to be heavily confounded by indication bias. As a result, the current literature still cannot offer a meaningful comparison between:

- REBOA vs. No REBOA for hemorrhagic shock

- REBOA vs. Open Aortic Occlusion for hemorrhagic shock

- REBOA has not been shown to be superior to preperitoneal pelvic packing in hemodynamically significant pelvic fractures.

- From large, prospective database studies:

- Time for successful REBOA placement is short and is likely similar to open aortic occlusion.

- Placement of REBOA in zone 1 or zone 3 increases systolic blood pressure.

- In cases of obstetric hemorrhage:

- There are no randomized controlled trials or prospective observational studies utilizing REBOA in the current obstetric literature.

- In a meta-analysis conducted by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, the evaluating committee made a conditional recommendation for the use of Zone 3 REBOA in cases of Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS).

Background:

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is a novel endovascular adjunct that is used to temporarily control non-compressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH) arising below the diaphragm. A catheter-based balloon is advanced retrograde from the common femoral artery into the aorta. The balloon is then inflated to occlude the aorta and stop blood flow. The effect is similar to cross-clamping the aorta during a resuscitative thoracotomy (RT). Although balloon occlusion of the aorta was described in the literature as early as 1954, its use has become increasingly popular since 2015. Increase in utilization is driven mainly by the introduction of a low-profile REBOA devices (ER-REBOA (Prytime Medical) and COBRA-OS (Front Line Medical Technologies)). Unlike the first generation REBOA catheters, which required open femoral access for placement of a 12 French introducer sheath, the lower profile REBOA catheters can be deployed through a either a 7 French sheath (ER-REBOA) or 4 French sheath (COBRA-OS) that may be placed percutaneously and does not require open femoral artery repair at the time of device removal. The technique is most commonly described in the trauma population, though REBOA use in non-trauma applications (e.g., obstetric emergencies, spontaneous intraabdominal hemorrhage, retroperitoneal sarcoma resection) has been described.

REBOA occlusion balloons may be placed in either the descending thoracic aorta between the left subclavian and celiac trunk (zone 1) or the infrarenal aorta (zone 3). Placement in zone 1 is intended for management of bleeding arising from the abdominal viscera or pelvic vessels. Placement in the zone 3 is intended only for management of bleeding from the pelvic vessels. The balloon should never be positioned between the celiac trunk and renal arteries (zone 2), as this may selectively increase the risk of visceral ischemic complications without decreasing bleeding.

Despite its renewed interest, there is only one published randomized control trial of endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta. 1 The UK REBOA study showed possible harm associated with REBOA use, however the study had important limitations . Additionally, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) sponsored a prospective cohort study that collected data on patients with NCTH undergoing either REBOA or RT. 2 However, study enrollment was completed in 2017, and the primary report does not offer a meaningful comparison to RT. Two prospective databases of REBOA procedures have been established that continue to enroll patients: the AAST AORTA registry in the United States and the ABO registry in Europe and Asia.3,4 Use of REBOA is not randomized, and case submission to the database is done voluntarily by participating institutions. Of the two, only the AAST AORTA registry offers a comparison to RT. The ABO registry does not compare REBOA to any other intervention.

Randomized Control Trial Data:

Data from the UK REBOA trial published in September 2024 was the first randomized control trial to evaluate outcomes in patients where REBOA was deployed in two trauma populations: standard of care vs standard of care + REBOA1. Outcomes of the trial were divided into two categories: clinical outcomes and economic outcomes. The primary clinical outcome was 90-day mortality (defined as death within 90 days of injury, before or after discharge from the hospital) and was aimed to capture any potential late harmful effects of REBOA. The primary economic outcome was lifetime incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year gained, modeled over a lifetime from a health and personal social services perspective. Secondary clinical outcomes included included 3-, 6- and 24-hour mortality, in-hospital mortality, 6- month mortality, length of stay (in hospital and ICU), 24-hour blood product use, need for hemorrhage control procedure (operation or angioembolization), time to commencement of hemorrhage control procedure, complications/safety data and functional outcome [measured using the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS-E) at discharge]. Secondary economic outcomes included 6-month costs from a health service and personal social services perspective, as well as quality of life [measured using EuroQol Group’s 5-dimension health status 5-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L)] at 6 months; and incremental cost per QALY gained at 6 months. The study showed that of the 46 participants allocated to SC + REBOA strategy, 25 (54%) died within 90 days. Using the minimally informative prior, the OR for 90-day mortality was 1.58 (95% CrI 0.72 to 3.52). The posterior probability of an OR > 1 (i.e. that REBOA was harmful) was 86.9%. For 3-, 6- and 24-hour mortality, there was an increased level of mortality in the SC + REBOA arm compared to SC with the greatest difference at 3 hours – 11 (24%) deaths in SC + REBOA compared with 2 (5%) deaths in SC, OR 4.25 95% CrI (1.33 to 15.99). For the adjusted analysis at other time points, the results were similar. Death due to hemorrhage was more common in the SC + REBOA strategy. The mean time from admission to hemorrhage control procedure (minutes) was 42 [standard deviation (SD) 121] in SC + REBOA and 28 (SD 41) in SC (MD 14.41 95% CrI –22.80 to 52.20). Additionally, there were 14 (30%) participants in SC + REBOA and 19 (43%) in SC that underwent a hemorrhage control procedure (OR 0.60, 95% CrI 0.26 to 1.37). Length of stay was shorted in the SC + REBOA group, which the authors attributed to increased incidence of early, in-hospital death. There were no major differences between blood product use, functional outcomes or complications.

This study had several limitations. First, this was a small trial (90 enrolled patients), reflecting the relative infrequency of exsanguinating traumatic hemorrhage in the UK. There were also some imbalances between the groups, particularly with regards to SBP on arrival in the ED (which was lower in patients allocated to the SC + REBOA strategy) and the presence of traumatic brain injuries (which were possibly more severe in patients allocated to the SC + REBOA strategy). Additionally, most of the participating centers had never used REBOA before in the trauma setting, and as such most of the insertions were performed by clinicians who had never used the technique before. Also, the clinical teams would have had little previous experience in managing patients once the device had been successfully inserted and inflated. Lastly, participating trauma centers’ research infrastructure limited the collection of more granular procedural or mechanistic data, such as blood pressure readings.

Prospective Data:

Data from the DoD NCTH study and the ABO registry show that REBOA can be placed rapidly and result in substantial improvement in hemodynamics. Median time from decision for AO to REBOA balloon inflation was 7 (IQR 5-11) minutes.2 Median increase in SBP was 41 mmHg in the DoD NCTH study and 40 mmHg in a 2018 review of the ABO registry.2,4

The initial report from the AAST AORTA registry, AORTA1, was conducted in 2016 and captured the first 114 aortic occlusion (AO) patients (REBOA 46, open AO 68).3 This study compared open AO to REBOA deployment in any zone and found no difference in time to AO (REBOA 6.6 ±5.6 minutes vs. open AO 7.2 ±15.1 min; p = 0.842) or mortality (REBOA 28.2% vs. open AO 16.1%; p = 0.120). Both techniques for AO were successful at improving hemodynamics and reached equivalent levels of hemodynamic stability following AO. However, the groups were not similar at baseline. The open AO group presented with greater physiologic derangement (i.e., higher heart rate, lower SBP) and was more likely to require CPR prior to AO. The second report from the AAST AORTA database, AORTA2, was conducted in 2018 and captured 285 AO patients (REBOA 83, open AO 202).5 However, this study compared only zone 1 REBOA to open AO (excluding the more stable zone 3 REBOA group with a primarily pelvic source of hemorrhage). Again, the groups were dissimilar at baseline, with the open AO group being younger, more likely to have a penetrating mechanism, and more hypotensive prior to AO. Overall, survival to discharge was greater in the REBOA group (9.6% vs 2.5%, p = 0.023), however this difference is driven primarily by the minority of patients who did not require CPR prior to AO (n = 56; REBOA 22.2% vs. open AO 3.4%; p = 0.048). The study showed no difference in survival to discharge in patients who received prehospital CPR (n = 172; REBOA 4.7% vs. open AO 2.3%; p = 0.60) or those who received CPR in the ED prior to AO (n = 57; REBOA 0% vs. open AO 2.3%; p = 1.000). The authors conclude that REBOA can confer a survival benefit over open AO in patients not requiring CPR, however because open AO was preferentially performed in patients presenting in cardiac arrest, this is likely the result of residual confounding from indication bias.

In 2022, a prospective observational study compared outcomes of AO via RT vs REBOA (Zone 1). Utilizing the AORTA registry, 991 patients treated in Level 1 trauma centers were included in the analysis with 306 undergoing Zone 1 REBOA placement and the remaining 685 undergoing RT. REBOA zone 1was associated with significantly lower mortality than RT (78.6% [44] vs 92.9% [52]; log-rank P = .02;Wilcoxon tests, P = .01; Cox proportional hazards model, P = .03). REBOA zone 1 resulted in more ventilator-free days and ICU-free days, although these differences were not significant.28

Lastly, Koh et al. conducted a prospective observational study that compared RT to REBOA in patients with hemorrhagic shock.24 Of the 452 patients enrolled in the study, 72 were included in the secondary analysis (26 underwent REBOA and 46 underwent RT). There was no difference in mortality between groups (88% vs. 93%, p = 0.767). However, time to aortic occlusion was longer in REBOA patients (7 vs. 4 minutes, p = 0.001) and they required more transfusions of red blood cells (4.5 vs. 2.5 units, p = 0.007) and plasma (3 vs. 1 unit, p = 0.032) in the emergency department. After adjusted analysis, mortality remained similar between groups (RR, 0.89; 95% confidence interval, 0.71–1.12, p = 0.304). Of note, technique for emergency hemorrhage control was not randomized, with selection bias likely accounting for differences seen in baseline characteristics among groups, specifically age and mechanism of injury.

Retrospective Data:

Of the retrospective studies published (excluding case reports and case series), no definitive conclusions about REBOA can be drawn.

REBOA vs. No REBOA (any indication)

Seven retrospective studies evaluated outcomes in trauma patients managed with REBOA compared to those managed without REBOA. 2015 and 2016 propensity-matched analyses of the Japan Trauma Data Bank (data years 2004-2011 and 2004-2014) and a 2019 propensity-matched analysis of the Trauma Quality Improvement Project (TQIP) database (data years 2015-2016) showed increased mortality in REBOA patients compared to no REBOA.6,7,8 Conversely, a 2018 Japanese single-center retrospective cohort study, a 2019 propensity-matched analysis of the Japan Trauma Data Bank, and a 2020 Colombian single-center retrospective cohort study show decreased mortality in the REBOA groups compared to no REBOA.9,10,11 However, a 2024 retrospective case control study utilizing the ACS-TQIP database compared outcomes in 35 propensity-matched patient pairs with severe pelvic fractures (AIS > 3) and lowest SBP < 90mmHg. This found no significant difference between REBOA vs non-REBOA in overall in-hospital mortality.26

REBOA vs Open Aortic Occlusion (AO)

Five retrospective studies have compared REBOA to open AO. A 2015 propensity-matched study of the Japan Trauma Data Bank showed lower mortality in the REBOA group.12 However, a 2017 propensity-matched database study of Japanese hospital diagnosis and procedure data showed no difference in mortality between REBOA and open AO.13 A 2020 single-center retrospective study of REBOA and open AO in Cali, Colombia also showed no difference in mortality.14 In 2022, a retrospective cohort study examined survival advantage in patients experiencing hemorrhagic shock with bleeding source below the aortic bifurcation who underwent Z3 REBOA vs open AO (RT). Overall mortality was lower in the Z3 REBOA group with similar complication profiles.25

REBOA vs Preperitoneal Packing (PPP)

Two retrospective studies have compared REBOA to PPP. A 2020 propensity-matched study of TQIP data (data years 2015-2017) showed lower mortality in the PPP group and no differences in blood product transfusion.15 However, a 2021 propensity-matched study of 2017 TQIP data showed lower mortality and less blood product transfusion in patients treated with REBOA.16

REBOA: Blunt vs Penetrating Mechanism

A single retrospective study has compared blunt vs penetrating mechanisms in patients undergoing REBOA placement. In 2022, a retrospective study utilizing the AORTA database showed that patient demographics, source of hemorrhage, catheter insertion setting and zone of deployment varied significantly by mechanism of injury. Patients with penetrating trauma undergoing REBOA were less likely than patients with blunt trauma undergoing REBOA insertion to improve or normalize their vital signs after REBOA insertion.27

Meta-Analytic Data:

Multiple systematic reviews with meta-analyses of the pooled data have been published. A 2017 systematic review includes three studies. 3, 12, 13, 17, 20 Meta-analysis of pooled data comparing REBOA to RT showed decreased mortality in the REBOA group. A 2018 systematic review included 89 studies, though the overwhelming majority of these were case reports, case series, or retrospective cohort studies of fewer than 20 patients. Its meta-analysis of the pooled data from three large retrospective studies (the DoD NCTH study,2 AORTA1,3 and a Japanese study comparing REBOA to RT+REBOA) showed decreased mortality in the REBOA group.17 Another systematic review was published in 2021, and included studies are limited to the large prospective and retrospective studies outlined above.18 Meta-analysis of the pooled data showed decreased mortality when REBOA was compared to RT but increased mortality when REBOA was compared to No REBOA (i.e., REBOA was worse than doing nothing but better than doing open AO).

A systematic review published in February 2021 including 35 studies involving 4073 patients showed REBOA to be associated with significant systolic blood pressure improvement, mortality benefit with REBOA and mortality improvement with REBOA compared to open aortic occlusion. Of note, the highest survival rate was seen in the analysis was in patients undergoing zone 3 AO.21 Lastly, a systematic review published in 2022 showed a reduced (although non-significant) risk of death for patients undergoing AO through REBOA, risk of death for patients undergoing AO through REBOA. 20

Two additional systematic reviews were published in 2022. The first systematic review included 35 studies and 4073 in the meta-analysis which looked at compared four groups: REBOA vs control (4), REBOA vs open aortic occlusion (7), REBOA vs partial occlusion (5) and complications (16). Of 4 studies comparing REBOA to non-REBOA controls, 2 found significant mortality benefit with REBOA. Significant mortality improvement with REBOA compared to open aortic occlusion was seen in 4 studies. In the few studies investigating zone placement, highest survival rate was seen in patients undergoing Zone 3. Overall, reports of complications directly related to overall REBOA use were relatively low.20 The subsequent systematic review included eight studies with 3215 patients in the meta-analysis. A significant survival benefit at 24 h (RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.27-0.79; I2: 55%; p = 0.005) and lower mean number of packed red blood cells were noted in the patients that had undergone REBOA placement in cases of significant abdominopelvic trauma (mean difference: – 3.02; 95% CI – 5.79 to – 0.25; p = 0.033).19

In 2024, the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma published an updated practice management guideline with associated systematic review and meta-analysis for the use of REBOA in surgical and trauma patients.22 Thirty-one studies were included in the meta-analysis. In unstable trauma patients with subdiaphragmatic bleeding, there was no significant difference in mortality among patients who were treated with REBOA vs no REBOA [OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.37, 2.04]. Subgroup analysis for individuals with pelvic fractures demonstrated higher mortality for REBOA vs no REBOA [OR=2.15, CI 1.35, 3.42]. In patients with TCA, pooled analysis demonstrated decreased mortality with REBOA vs resuscitative thoracotomy (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.15, 0.69). Compared with no REBOA, prophylactic placement of REBOA prior to cesarean section in PAS had lower intra-operative blood loss [-1.06 L, CI -1.57 to -0.56] and red blood cell transfusion [-2.44 units, CI -4.27 to -0.62]. Overall, the level of evidence was assessed by the working group as very low.

Unfortunately, each of these systematic reviews is limited by study heterogeneity (I2 as high as 87%), and the included studies are limited by indication bias.

Obstetric Hemorrhage/Placenta Accreta Spectrum (PAS):

Randomized Control Trial Data

To date, no randomized control trials utilizing REBOA in cases of obstetric hemorrhage/PAS have been performed.

Meta-Analytic Data

One systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of prophylactic balloon occlusion of the aorta during cesarean section (CS) in improving maternal outcomes in PAS patients.22 Of the 776 articles identified, a total of 11 retrospective articles involving the application of REBOA for patients with PAS disorder were included. Of the 11, 7 compared intraoperative hemorrhage between the aortic balloon occlusion of the aorta (AABO) and No AABO groups. The prophylactic use of AABO before surgery significantly reduced the blood loss volume compared with no AABO (MD -1480 mL, 95% CI -1806 to − 1154 mL, P < 0.001). Additionally, blood transfusion volume was reported in 6 studies; overall, patients who underwent AABO required fewer PRBC unit transfusions than those who did not undergo AABO (MD -1125 mL, 95% CI -1264 to − 987 mL, P < 0.001). Seven articles listed a lower operative time in the AABO group (MD − 29.23 min, 95% CI -46.04 to − 12.42 min, P < 0.001) and 6 studies showed a significant reduction in the postoperative hospitalization duration with AABO (MD -1.35 days, 95% CI -2.40 to − 0.31 days, P = 0.01).

While the above study doesn’t specify the aortic balloon occlusion catheter evaluated, systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, the final PICO addressed whether or not hemodynamically stable patients with anticipated subdiaphragmatic bleeding due to PAS should undergo prophylactic REBOA placement, prior to definitive hemostatic procedures, to decrease blood transfusion requirements and blood loss.23 On pooled analysis from over 10 studies, prophylactic use of REBOA prior to cesarean section + hysterectomy in patients with PAS led to reduction of packed red blood cell transfusion by close to 3 units and EBL by 1 L. Additionally noted was a benefit of prophylactic over emergent approach to obtaining femoral arterial access with a likely lower incidence of access site complications. As a result, the committee made a conditional recommendation for the use of REBOA in this patient population.

Search Strategy

| Search | Database | Search Term | Limits | # of Articles | # Excluded | # Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (trauma[Title/Abstract]) | Human, Randomized control trial | 5 | 4 (2 not human; 1 not RCT; 1 prehospital placement) |

1 |

| 2 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (trauma[Title/Abstract]) | Human, Systematic review | 16 | 11 (2 not REBOA; 1 not trauma; 1 prehospital care; 3 complications only; 3 no comparator group; 1 included animal models) |

5 |

| 3 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (trauma[Title/Abstract]) | Human | 350 | 327 (137 review, case report, or case series; 48 no data; 32 non generalizable/single center; 27 no comparator; 21 not trauma; 12 partial REBOA or Z1 vs Z3; 7 prehospital; 13 not human; 2 pediatric; 3 secondary review of UK-REBOA trial; 5 duplicate; 5 unclear research strategy; 5 no REBOA in data; 10 complication-focused) | 23 |

| 4 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (obstetric[Title/Abstract]) | Human, Randomized control trial | 0 | N/A | 0 |

| 5 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (obstetric[Title/Abstract]) | Human, Systematic Review | 3 | 1 non-OB; 2 duplicated in PAS group | 0 |

| 6 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (obstetric[Title/Abstract]) | Human | 17 | 2-no REBOA deployment; 2 non-OB focused; 1 case report; 2 radiology-focused; 2 complication-focused; 8 duplicated in PAS group | 0 |

| 7 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (placenta accreta spectrum[Title/Abstract]) | Human, Randomized control trial | 0 | N/A | 0 |

| 8 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (placenta accreta spectrum[Title/Abstract]) | Human, Systematic Review | 2 | 1 non-REBOA, 1 IR focused | 0 |

| 9 | PubMed | (((REBOA[Title/Abstract]) OR (balloon occlusion[Title/Abstract])) AND (aorta[Title/Abstract])) AND (placenta accreta spectrum[Title/Abstract]) | Human | 29 | 1 no REBOA deployment 2 case reports; 1 Zone 3A vs 3B; 6 radiology-focused; 4 anesthesia-focused; 4 guideline-focused; 1 complication focused |

0 |

References

- Jansen JO, Hudson J, Kennedy C, Cochran C, MacLennan G, Gillies K, Lendrum R, Sadek S, Boyers D, Ferry G, Lawrie L, Nath M, Cotton S, Wileman S, Forrest M, Brohi K, Harris T, Lecky F, Moran C, Morrison JJ, Norrie J, Paterson A, Tai N, Welch N, Campbell MK; UK-REBOA Study Group. The UK resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in trauma patients with life-threatening torso hemorrhage: the (UK-REBOA) multicentre RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2024 Sep;28(54):1-122. doi: 10.3310/LTYV4082. PMID: 39259521; PMCID: PMC11418015.

- Moore LJ, Fox EE, Meyer DE, Wade CE, Podbielski JM, Xu X, Morrison JJ, Scalea T, Fox CJ, Moore EE, Morse BC, Inaba K, Bulger EM, Holcomb JB. Prospective Observational Evaluation of the ER-REBOA Catheter at 6 U.S. Trauma Centers. Ann Surg. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004055. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33064384.

- DuBose JJ, Scalea TM, Brenner M, Skiada D, Inaba K, Cannon J, Moore L, Holcomb J, Turay D, Arbabi CN, Kirkpatrick A, Xiao J, Skarupa D, Poulin N; AAST AORTA Study Group. The AAST prospective Aortic Occlusion for Resuscitation in Trauma and Acute Care Surgery (AORTA) registry: Data on contemporary utilization and outcomes of aortic occlusion and resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016 Sep;81(3):409-19. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001079. PMID: 27050883.

- Sadeghi M, Nilsson KF, Larzon T, Pirouzram A, Toivola A, Skoog P, Idoguchi K, Kon Y, Ishida T, Matsumara Y, Matsumoto J, Reva V, Maszkowski M, Bersztel A, Caragounis E, Falkenberg M, Handolin L, Kessel B, Hebron D, Coccolini F, Ansaloni L, Madurska MJ, Morrison JJ, Hörer TM. The use of aortic balloon occlusion in traumatic shock: first report from the ABO trauma registry. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018 Aug;44(4):491-501. doi: 10.1007/s00068-017-0813-7. Epub 2017 Aug 11. PMID: 28801841; PMCID: PMC6096626.

- Brenner M, Inaba K, Aiolfi A, DuBose J, Fabian T, Bee T, Holcomb JB, Moore L, Skarupa D, Scalea TM; AAST AORTA Study Group. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta and Resuscitative Thoracotomy in Select Patients with Hemorrhagic Shock: Early Results from the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma’s Aortic Occlusion in Resuscitation for Trauma and Acute Care Surgery Registry. J Am Coll Surg. 2018 May;226(5):730-740. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.01.044. Epub 2018 Feb 6. Erratum in: J Am Coll Surg. 2018 Oct;227(4):484. PMID: 29421694.

- Norii T, Crandall C, Terasaka Y. Survival of severe blunt trauma patients treated with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta compared with propensity score-adjusted untreated patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Apr;78(4):721-8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000578. PMID: 25742248.

- Inoue J, Shiraishi A, Yoshiyuki A, Haruta K, Matsui H, Otomo Y. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta might be dangerous in patients with severe torso trauma: A propensity score analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016 Apr;80(4):559-66; discussion 566-7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000968. PMID: 26808039.

- Joseph B, Zeeshan M, Sakran JV, Hamidi M, Kulvatunyou N, Khan M, O’Keeffe T, Rhee P. Nationwide Analysis of Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in Civilian Trauma. JAMA Surg. 2019 Jun 1;154(6):500-508. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.0096. PMID: 30892574; PMCID: PMC6584250.

- Otsuka H, Sato T, Sakurai K, Aoki H, Yamagiwa T, Iizuka S, Inokuchi S. Effect of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in hemodynamically unstable patients with multiple severe torso trauma: a retrospective study. World J Emerg Surg. 2018 Oct 25;13:49. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0210-5. PMID: 30386415; PMCID: PMC6202823.

- Yamamoto R, Cestero RF, Suzuki M, Funabiki T, Sasaki J. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) is associated with improved survival in severely injured patients: A propensity score matching analysis. Am J Surg. 2019 Dec;218(6):1162-1168. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.09.007. Epub 2019 Sep 13. PMID: 31540683.

- García AF, Manzano-Nunez R, Orlas CP, Ruiz-Yucuma J, Londoño A, Salazar C, Melendez J, Sánchez ÁI, Puyana JC, Ordoñez CA. Association of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) and mortality in penetrating trauma patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2020 Apr 16. doi: 10.1007/s00068-020-01370-9. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32300850.

- Abe T, Uchida M, Nagata I, Saitoh D, Tamiya N. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta versus aortic cross clamping among patients with critical trauma: a nationwide cohort study in Japan. Crit Care. 2016 Dec 15;20(1):400. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1577-x. Erratum in: Crit Care. 2017 Feb 22;21(1):41. PMID: 27978846; PMCID: PMC5159991.

- Aso S, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta or resuscitative thoracotomy with aortic clamping for noncompressible torso hemorrhage: A retrospective nationwide study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017 May;82(5):910-914. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001345. PMID: 28430760.

- Ordoñez CA, Rodríguez F, Orlas CP, Parra MW, Caicedo Y, Guzmán M, Serna JJ, Salcedo A, Zogg CK, Herrera-Escobar JP, Meléndez JJ, Angamarca E, Serna CA, Martínez D, García AF, Brenner M. The critical threshold value of systolic blood pressure for aortic occlusion in trauma patients in profound hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020 Dec;89(6):1107-1113. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002935. PMID: 32925582.

- Mikdad S, van Erp IAM, Moheb ME, Fawley J, Saillant N, King DR, Kaafarani HMA, Velmahos G, Mendoza AE. Pre-peritoneal pelvic packing for early hemorrhage control reduces mortality compared to resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in severe blunt pelvic trauma patients: A nationwide analysis. Injury. 2020 Aug;51(8):1834-1839. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2020.06.003. Epub 2020 Jun 6. PMID: 32564964.

- Asmar S, Bible L, Chehab M, Tang A, Khurrum M, Douglas M, Castanon L, Kulvatunyou N, Joseph B. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta vs Pre-Peritoneal Packing in Patients with Pelvic Fracture. J Am Coll Surg. 2021 Jan;232(1):17-26.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.08.763. Epub 2020 Oct 3. PMID: 33022396.

- Borger van der Burg BLS, van Dongen TTCF, Morrison JJ, Hedeman Joosten PPA, DuBose JJ, Hörer TM, Hoencamp R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in the management of major exsanguination. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018 Aug;44(4):535-550. doi: 10.1007/s00068-018-0959-y. Epub 2018 May 21. PMID: 29785654; PMCID: PMC6096615.

- Castellini G, Gianola S, Biffi A, Porcu G, Fabbri A, Ruggieri MP, Coniglio C, Napoletano A, Coclite D, D’Angelo D, Fauci AJ, Iacorossi L, Latina R, Salomone K, Gupta S, Iannone P, Chiara O; Italian National Institute of Health guideline working group on Major Trauma. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in patients with major trauma and uncontrolled haemorrhagic shock: a systematic review with meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2021 Aug 12;16(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s13017-021-00386-9. PMID: 34384452; PMCID: PMC8358549.

- Granieri S, Frassini S, Cimbanassi S, Bonomi A, Paleino S, Lomaglio L, Chierici A, Bruno F, Biondi R, Di Saverio S, Khan M, Cotsoglou C. Impact of resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) in traumatic abdominal and pelvic exsanguination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022 Oct;48(5):3561-3574. doi: 10.1007/s00068-022-01955-6. Epub 2022 Mar 20. PMID: 35307763.

- Kinslow K, Shepherd A, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of Aorta: A Systematic Review. Am Surg. 2022 Feb;88(2):289-296. doi: 10.1177/0003134820972985. Epub 2021 Feb 19. PMID: 33605780.

- Chen L, Wang X, Wang H, Li Q, Shan N, Qi H. Clinical evaluation of prophylactic abdominal aortic balloon occlusion in patients with placenta accreta: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Jan 15;19(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2175-0. PMID: 30646863.

- Harfouche MN, Bugaev N, Como JJ, Fraser DR, McNickle AG, Golani G, Johnson BP, Hojman H, Abdel-Aziz H, Sawhney JS, Cullinane DC, Lorch S, Haut ER, Fox N, Magder LS, Kasotakis G. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in surgical and trauma patients: a systematic review, meta-analysis and practice management guideline from the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2025 Mar 28;10(1):e001730. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2024-001730. PMID: 40166770.

- Kyozuka H, Yasuda S, Murata T, Sugeno M, Fukuda T, Yamaguchi A, Nomura Y, Fujimori K. Prophylactic resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta use during cesarean hysterectomy for placenta accreta spectrum: a retrospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023 Dec;36(2):2232073. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2023.2232073. PMID: 37408127.

- Koh EY, Fox EE, Wade CE, Scalea TM, Fox CJ, Moore EE, Morse BC, Inaba K, Bulger EM, Meyer DE. Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta and resuscitative thoracotomy are associated with similar outcomes in traumatic cardiac arrest. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2023 Dec 1;95(6):912-917. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004094. Epub 2023 Jun 29. PMID: 37381147; PMCID: PMC10755074.

- Bini JK, Hardman C, Morrison J, Scalea TM, Moore LJ, Podbielski JM, Inaba K, Piccinini A, Kauvar DS, Cannon J, Spalding C, Fox C, Moore E, DuBose JJ; AAST AORTA Study Group. Survival benefit for pelvic trauma patients undergoing Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta: Results of the AAST Aortic Occlusion for Resuscitation in Trauma Acute Care Surgery (AORTA) Registry. Injury. 2022 Jun;53(6):2126-2132. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2022.03.005. Epub 2022 Mar 12. PMID: 35341594.

- Ahmed N, Kuo YH. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of The Aorta (REBOA) And Mortality in Hemorrhagic Shock Associated with Severe Pelvic Fracture: a National Data Analysis. BMC Emerg Med. 2024 Jun 24;24(1):104. doi: 10.1186/s12873-024-01020-y. PMID: 38910235; PMCID: PMC11194952.

- Schellenberg M, Owattanapanich N, DuBose JJ, Brenner M, Magee GA, Moore LJ, Scalea T, Inaba K; AAST PROOVIT Study Group. Resuscitative Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta in Penetrating Trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 2022 May 1;234(5):872-880. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000000136. PMID: 35426399.

- Cralley AL, Vigneshwar N, Moore EE, Dubose J, Brenner ML, Sauaia A; AAST AORTA Study Group. Zone 1 Endovascular Balloon Occlusion of the Aorta vs Resuscitative Thoracotomy for Patient Resuscitation After Severe Hemorrhagic Shock. JAMA Surg. 2023 Feb 1;158(2):140-150. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.6393. PMID: 36542395; PMCID: PMC9856952.