Lorenz Lab

Michael Lorenz, Ph.D.

Understanding the molecular basis of fungal infections

Infectious diseases are one of the most challenging aspects of microbiology. Their toll on human health remains immense and emerging drug resistance puts us at risk of backsliding on a century of progress in treating these diseases. Fungi are often overlooked as infectious agents, despite causing a spectrum of diseases ranging from mild and common to life-threatening infections responsible for over one million deaths per year. Candida albicans is the most important fungal pathogen, as it is capable of infecting virtually any body site, including the mouth and throat (oral thrush) and the genital tract (vaginal yeast infections), but our primary interest is in the life threatening infections that occur mostly in hospitalized patients with weakened immune systems. Increasingly frequent, about 40% of those who get disseminated candidiasis will die, making it as deadly as HIV/AIDS and MRSA in this country. Unlike these infections, however, patients acquire candidiasis from themselves: C. albicans is also a universal part of the human microbiota, existing harmlessly in most of us.

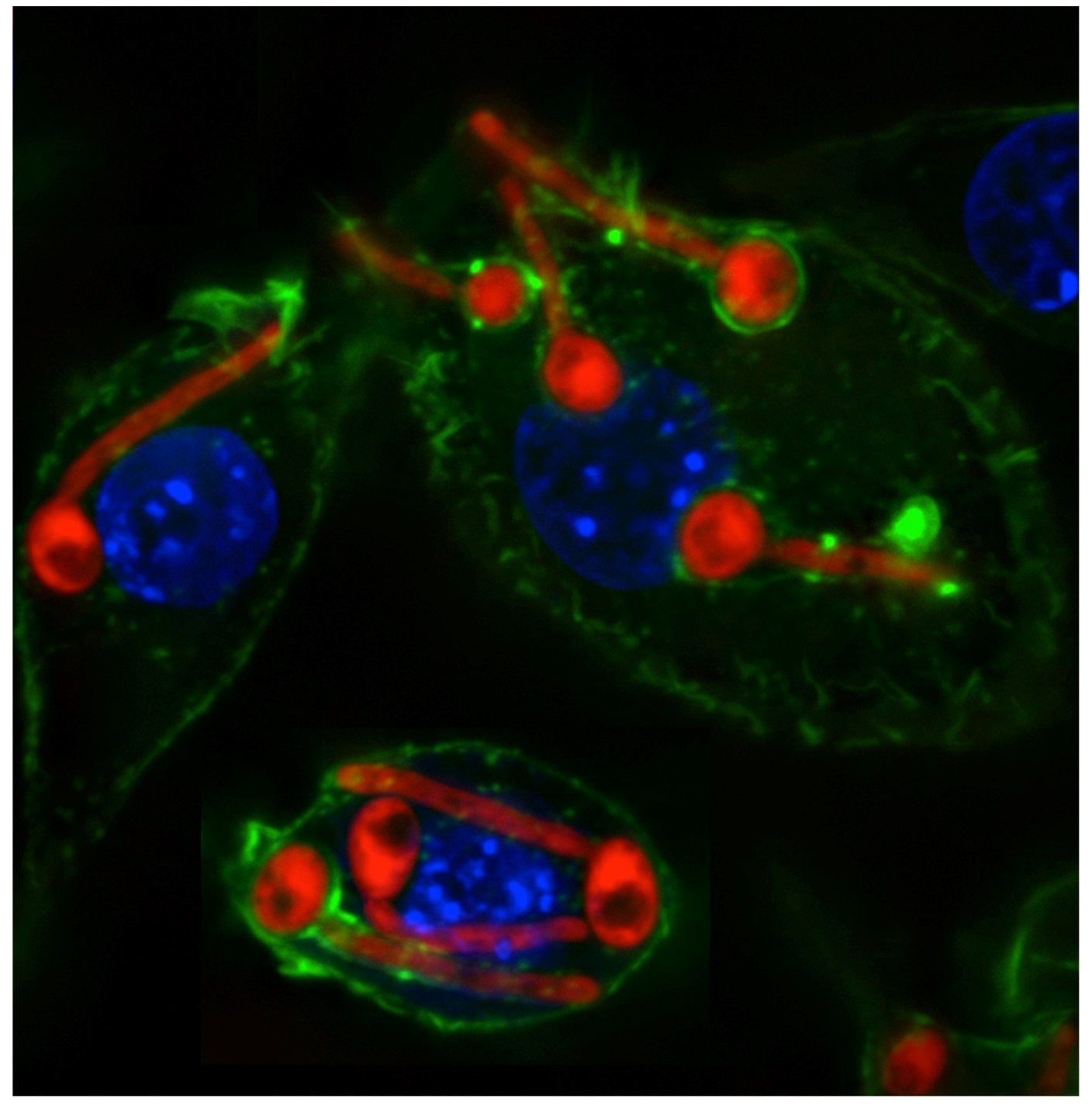

Healthy individuals are protected from candidiasis by their innate immune system and our lab studies the dynamic and fascinating interaction of C. albicans with phagocytic cells. C. albicans dramatically alters macrophage function, by inhibiting production of antimicrobial compounds like nitric oxide and remodeling the phagolysosome, eventually allowing the fungal cell to adopt an filamentous morphology and escape the phagocyte. We seek to understand how this important pathogen has adapted its metabolism, stress responses, and physiology to contribute to its ability to cause disease, with an ultimate goal of identifying ways to better diagnose and treat these infections.

The dynamic interaction of Candida albicans with mammalian macrophages. C. albicans is stained in red, the macrophage actin cytoskeleton in green, and the macrophage nuclei in blue.

(Photo credit: Dr. Pedro Miramón)