Facial Reanimation Surgery Brightens a Young Boy’s Future

It been a year since Matthew La Macchia was attacked by an American bulldog while playing with friends just down the street from his home. Matthew, who was eight years old at the time, suffered six wounds on the scalp and seven wounds on his face, including a torn facial nerve that caused facial paralysis on the left side.

“Everything happened so fast,” recalls Matthew’s father James La Macchia. “When his friends’ grandmother opened the door to check on her grandkids, the dog ran out and went straight for Matthew. The dog bit him on the butt and dragged him to the ground. Matthew stood up, and the dog bit him on the belly and knocked him down again. When he got up the second time, the dog went for his head. His entire face was bloody, and one wound looked like a big conglomeration of missing flesh.”

Matthew’s older brother Nicholas threw himself down on his brother, using his own body as a protective shield. He took off his shirt, wrapped it around Matthew’s bleeding head and led him home, yelling to a passerby to call 911.

The EMS team took Matthew to Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, where he was initially treated with wound irrigation and debridement, and laceration repair by on-call otorhinolaryngologist Etan Weinstock, MD, an assistant professor in the department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) Medical School. Noting that Matthew had facial paralysis on the left side, Dr. Weinstock referred him to Tang Ho, MD, a fellowship-trained facial plastic and reconstructive surgeon in the department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, for further outpatient evaluation and treatment.

Dr. Ho first saw Matthew approximately one month after his injury. “We gave him some time to heal because in cases of traumatic facial paralysis where the extent of facial nerve injury is uncertain, function may return on its own,” he says. “But the paralysis persisted in the forehead area on the left side, and further nerve function studies showed that there was no neural stimulation to the forehead. When we talked to the family about facial reanimation surgery, we cautioned them that the outcome can be uncertain. It might not be possible to locate all the nerve branches given the amount of scarring, and nerve function recovery is unpredictable. But the best chance we have of restoring facial movement is to locate and reconnect the severed nerve.”

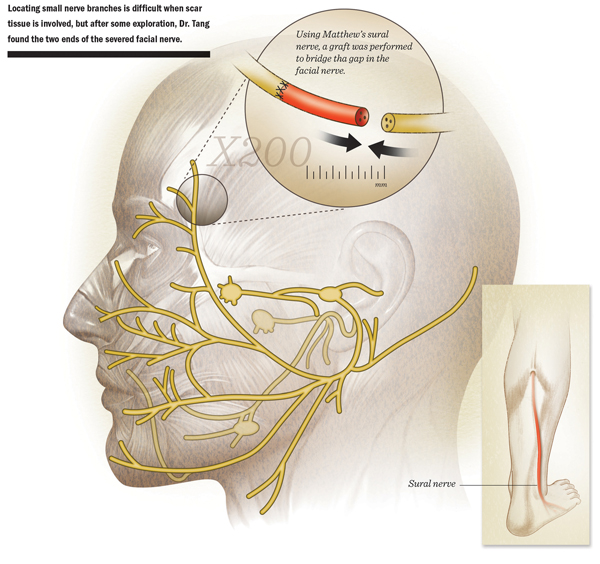

A few weeks later, Dr. Ho brought Matthew to the OR for formal facial re-animation surgery. “We explored along the previous scar to minimize the visibility of the incision,” says Dr. Ho, who is an assistant professor in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at McGovern Medical School. “It can be difficult to explore for such small nerve branches when scar tissue is involved, but after some searching, we were able to locate the two ends of the severed facial nerve, along with some of the nerve branches.”

Under visualization provided by a microscope, , Dr. Ho performed a nerve graft to bridge the gap in the facial nerve. A branch of Matthew’s sural nerve served as the donor, since the it was a good size match for the facial nerve. In addition, Dr. Ho completed a direct muscular neurotization with the nerve graft.

Following the surgery, Dr. Ho advised Matthew’s parents to give the nerve six months to regenerate, but at three months after the surgery, they had already noticed some improvement of the facial tone at rest. At six months, he was able to move his forehead again.

“Now, nearly a year out from surgery, even though Matthew still has a slight weakness on the left side, there’s been dramatic improvement,” Dr. Ho says. “There are many procedures that can be performed to correct facial symmetry after this kind of injury, but the best results are achieved when we can locate and repair the severed nerve. Facial paralysis can be extremely debilitating for patients and carries with it a social stigma that makes daily normal social interaction challenging for patients, particularly for children. I think the improvement in facial function we’ve seen with Matthew’s procedure is going to give him a better chance of having a normal childhood.”

“The results with secondary facial nerve repair can be unpredictable,” he adds. “However, we’re fortunate that Matthew has made tremendous strides in facial nerve function recovery, at a much faster pace than we would have anticipated. Without a doubt, his family’s support contributes to the favorable outcomes we have seen here.”

“Dr. Ho did a great job,” James La Macchia says. “He was always cautiously optimistic, and never promised that things would be great. He was pleasantly surprised at the first return visit three months after the surgery, when Matthew could move his forehead. The whole experience was traumatic, but the people at the hospital were as elegantly gentle as you could possibly imagine. They sincerely care.”