Genetic testing alerts family to lurking danger

More than a decade after the death of Matt’s father, in 2005 doctors discovered Matt’s 11-month-old son—rushed to the hospital after turning blue—had an enlarged aorta. Also known as thoracic aortic aneurysm, the condition can be deadly if left undiagnosed and untreated.

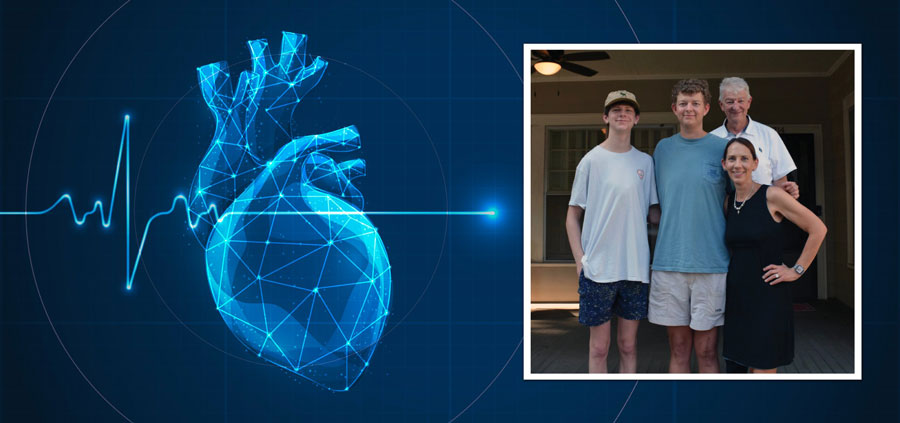

Because thoracic aortic aneurysms can run in families, Matt and his wife decided to have their other son tested. To their surprise, he was also diagnosed with the condition. Soon after, so was Matt.

The Herlevic family was put in touch with Dianna Milewicz, MD, PhD, professor and director of the Division of Medical Genetics, who wanted to know what was causing the inherited form of thoracic aortic aneurysms in Matt’s family. Milewicz directs The John Ritter Research Program in Aortic and Vascular Diseases at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, which works to prevent deaths due to thoracic aortic disease by identifying genes and other risk factors for the disease. After years of research, she discovered the culprit in the Herlevic case: a mutation in the TGFB2 gene.

“Thoracic aortic aneurysms can be passed from one generation to the next. They do not cause symptoms, but as they enlarge, the risk of an acute aortic dissection—which is often deadly—increases,” she said. “If we can diagnose the aneurysm, the aorta can be surgically repaired, preventing dissections. If we know thoracic aortic aneurysms are running in a family, we can prevent the deadly dissections through genetic testing, imaging the enlarged aorta, and surgery.”

Six more of Matt’s immediate family members have been tested for and diagnosed with the TGFB2 mutation, bringing the total to nine. Members of the Herlevic family receive frequent monitoring from their physicians to detect any potential danger of an aorta rupture and take action to prevent it.

Milewicz’s research revealed medications that can slow the progression of thoracic aortic aneurysm, while a surgical procedure—which Matt underwent in 2016—can repair the defect.

“I lived every day to the fullest, knowing one day I would have to have surgery,” he said. “I have yearly checkups, I take my meds, and I push forward.”

Discoveries like the TGFB2 gene require a significant investment of resources, from advanced equipment to daily essential supplies for experiments. While federal agencies like the National Institutes of Health provide large research grants, they often do not cover all of a project’s expenses—and researchers have to conduct initial proof-of-concept studies to successfully apply for these grants.

Philanthropic support of initiatives like The John Ritter Research Program provides the funds for Milewicz and other cardiovascular researchers at McGovern Medical School to continue their lifesaving work. In particular, her research on thoracic aortic aneurysms received significant funding from individuals and organizations like The John Ritter Foundation for Aortic Health.

“I am very grateful to everyone who has given to support our research program,” Milewicz said. “Before these discoveries, so many people lived at serious risk of sudden death without any way of knowing. But thanks to our donors, the outlook is completely different now.”