A Novel Lymphatic Imaging System and a Disease-focused Treatment Team Improve Survivorship in Head and Neck Cancer

Oropharyngeal cancers are still relatively uncommon, but those associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) are on the rise. Kelly Jones presented as a typical case in this relatively new category of oropharyngeal cancer patient: a 43-year-old non-smoker with previously undiagnosed HPV infection. In 2013, he noticed a neck mass that proved malignant on biopsy. Now, two and a half years later, after transoral robotic surgery (TORS), chemotherapy and radiation therapy, Jones is cured.

What is atypical about his case is his participation in a one-of-a-kind study of the workings of the lymphatic system in head and neck cancer patients, currently under way at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center and University of Texas the John P. and Kathrine G. McGovern Medical School at Houston. Jones’ participation, along with that of 19 other patients, has allowed physicians to use a novel lymphatic imaging system to guide lymphedema treatment and improve quality of life in head and neck cancer survivorship. Patients also benefit from access to a multidisciplinary, disease-focused treatment team that provides the full spectrum of care, from in-office diagnosis and surgery to cancer rehabilitation and support for return to the community.

After Jones found a neck mass in June 2013, an ENT in Deer Park, TX, referred him to Ron Karni, MD, who specializes in TORS and is chief of the division of Head and Neck Surgical Oncology in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at the McGovern Medical School. During the office visit, Dr. Karni performed an ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy. Further evaluation confirmed a WHO Stage 4 squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil and tongue that had spread to the lymph nodes in the neck.

“As soon as I found the lump, I had a bad feeling,” Jones says. “But I was hoping for better news. We went in optimistic. He stuck a needle in my neck and confirmed my suspicions. In that single moment, your life changes forever.”After describing the benefits of transoral robotic surgery and explaining what Jones could expect following surgery and radiation therapy, Dr. Karni asked him if he would be willing to participate in a clinical trial to help researchers gain new information about the effects of treatment on the lymphatic system with the goal of improving quality of life down the road. Jones was among the first patients to participate in the study, which was funded by a grant from the Cancer Prevention Institute of Texas (CPRIT).

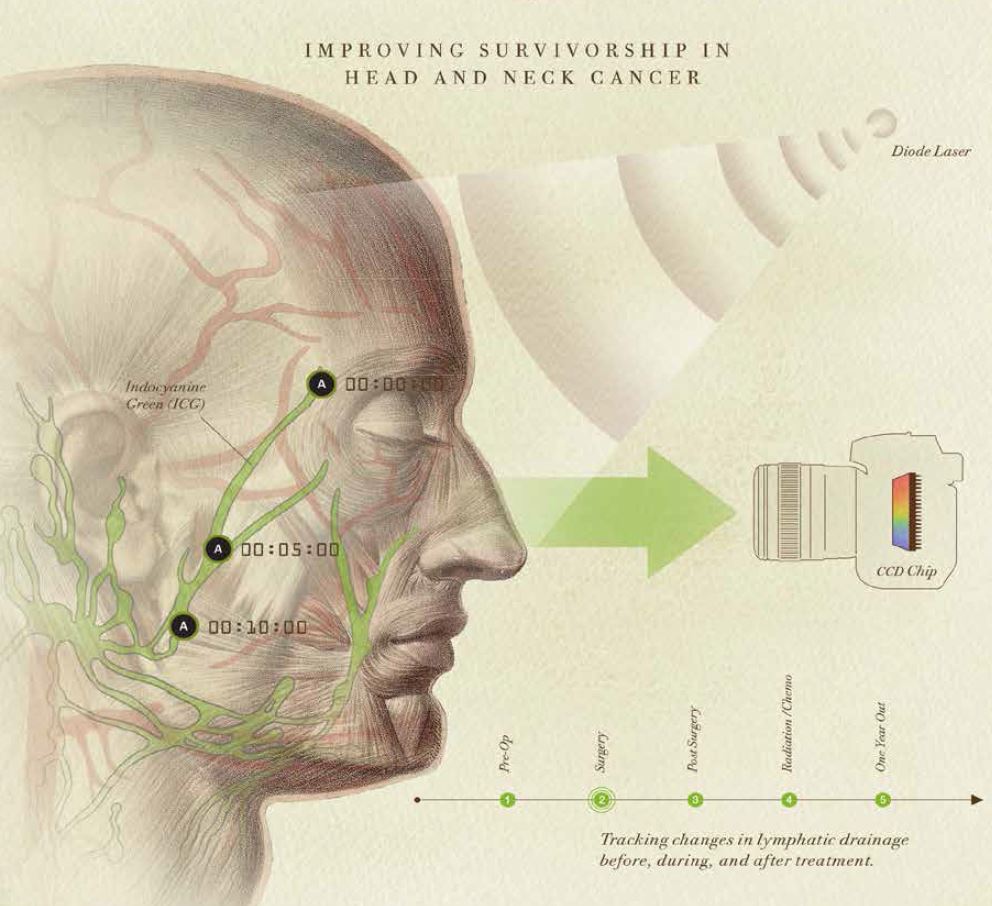

The grant was awarded to principal investigator Eva Sevick, PhD, professor of molecular medicine and Kinder Chair at the Brown Foundation Institute of Molecular Medicine for the Prevention of Human Diseases, whose research team adapted night-goggle technology used by the military to visualize the workings of the lymphatic system in head and neck cancer patients. Dr. Karni and research engineer I-Chih Tan, PhD, are co-investigators for the trial.

“By adapting infrared night-goggle technology in a new way, we can visualize things we’ve never before seen in either animals or human beings,” Dr. Sevick says. “When we first saw it work, we thought, ‘Eureka! We’re actually seeing the workings of the lymphatic system in living beings.’”

Dr. Sevick pioneered the development of near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence optical imaging and tomography for molecular imaging. For the CPRIT-funded study, she and Dr. Tan took night-goggle technology and developed it into a detector – a very small device that uses a charge-coupled device (CCD) similar to the chip in a digital camera.

They also developed new dyes that fluoresce. “Near-infrared light propagates through several centimeters of tissue,” she says. “It’s non-ionizing with no exposure to radioactivity. If we inject a tiny bit of fluorescent dye, it’s taken up by the lymphatic system, allowing us to see the lymph vessel segments pulsing in real time, like little hearts, as they pump lymph through the body. Based on what we discover in the clinical trial, we’re hoping to be able to treat head and neck cancer successfully in a more efficient way that improves the overall quality of life for patients.”

Like other patients who’ve undergone the study, Jones was imaged prior to surgery in Dr. Karni’s office using the technology developed in Dr. Sevick’s lab. A near-infrared fluorescence snapshot was taken after surgery, after radiation therapy and every three months for a year following the initiation of treatment.

“We inject a dye that’s taken up by the lymphatics and illuminate it with a laser diode, which excites the dye and causes it to fluoresce,” Dr. Sevick says. “We can collect the very dim fluorescence with our military-grade technology and then watch how the lymphatics move.”

Jones found the experience fascinating. “You sit in a big dentist chair and get comfortable,” he says. “They take several snapshots of your face and side views using a camera with a telephoto lens and fancy attachments hooked to a computer screen. The doctor comes in and injects you with dye in eight or 10 spots around the neck, ears and cheeks and then monitors the flow with the equipment. It took about an hour each time. I could look at the computer screen and see the lymph pumping. It was cool to watch.”

Following treatment for head and neck cancer, 50 percent of patients suffer profound lymphedema, swelling due to blockage of the lymph vessels that drain fluid from tissues throughout the body and allow immune cells to travel where they are needed. “During treatment for head and neck cancer, the lymphatic system receives three types of injuries,” Dr. Karni says. “The first is caused by the tumor itself, which infiltrates the lymph system and impedes circulation. Surgery to remove all the lymph nodes in the neck is an assault on the body. The third injury is radiation. Almost all patients with advanced head and neck cancer receive radiation therapy, which seals the lymphatics. Patients undergoing treatment for head and neck cancer usually have fibrosis, very limited movement of the head and neck and lymphedema, which causes debilitation and deformity. We don’t know exactly why the lymph vessels stop pumping.”

Jones was among the patients who suffered lymphedema after treatment. “I told Dr. Karni at the beginning that it wouldn’t phase me,” he says. “I race motocross and I’ve broken bones. I can take pain. But this was the toughest thing I’ve ever done. I lost my beard, and the turkey neck was very frustrating. I had to learn to swallow again. Dr. Karni told me I just had to be patient–that I would get through it–and I did.”

Jones completed his last study with Dr. Sevick in late winter of 2014. “We learned a lot watching the lymphatics of Kelly’s neck change,” Dr. Karni says. “Normally they flow in reliable ways but after radiation therapy we could see dermal backflow. If manual drainage for lymphedema therapy is done in the wrong direction, the therapist is basically giving the patient a nice massage but not really treating the condition. By knowing the lymphatic patterns of each individual patient, we can provide better treatment for lymphedema.”

They also discovered that lymphedema typically occurs about six weeks after radiation therapy. “We expect to get a treasure trove of data about how lymphatic pathways reorient around the surgical and radiation site,” Dr. Karni says. “If all this works as well as we think it will, we’ll be better able to stage head and neck cancer. If we can ultimately identify the lymph nodes that are cancer positive, remove them and leave the others, we may become more efficient at treatment and reduce the risk of lymphedema.”

The researchers would also like to learn why half of patients treated for head and neck cancer get lymphedema and half don’t. All of the study subjects who underwent radiation therapy had a dramatic change in lymphatics, but not all of them developed lymphedema.

Dr. Sevick believes the study has implications for patients with other types of cancer as well. “It’s an incredible opportunity for us to impact the lives of our cancer survivors,” she says. “The incidence of head and neck cancer is increasing because of HPV. We’re seeing younger and younger people with the disease, and lost productivity due to disease has a significant economic impact. We’re working to mitigate survivorship disease.”

Both Dr. Sevick and Dr. Karni note that head and neck cancer survivorship issues have been overlooked until recently. “As we become more efficient at curing cancer, we have to start looking at the aftermath of treatment,” Dr. Karni says. “Our patients are cured, but living with lymphedema is very expensive, and often people don’t know where to go for help. We want patients to know that if they get treatment for lymphedema early – even before they have surgery and radiation – they’ll have a better outcome.”

Both Dr. Sevick and Dr. Karni note that head and neck cancer survivorship issues have been overlooked until recently. “As we become more efficient at curing cancer, we have to start looking at the aftermath of treatment,” Dr. Karni says. “Our patients are cured, but living with lymphedema is very expensive, and often people don’t know where to go for help. We want patients to know that if they get treatment for lymphedema early – even before they have surgery and radiation – they’ll have a better outcome.”

To that end, Dr. Karni forged a relationship with cancer rehabilitation specialist Carolina Gutiérrez, MD, a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the McGovern Medical School and a consulting physician at TIRR Memorial Hermann. The two physicians have been seeing patients together in clinic for more than a year, along with Tang Ho, MD, who is chief of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery and an assistant professor in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.

“When we see a cancer patient, we’re very aware that we’re seeing an individual who has a life beyond diagnosis and treatment,” Dr. Gutiérrez says. “In one session I do a baseline assessment looking at the whole person, and make referrals for prehabilitation to optimize the outcome and help improve quality of life after treatment. Is the patient deconditioned? Those who are may want to start an exercise program to help combat fatigue. Do they smoke and want to quit? We can connect them with the resources they need. In addition to fatigue, the main side effects of radiation in patients with head and neck cancer are difficulty swallowing and loss of range of motion in the neck and shoulder. To improve swallowing, we arrange a consultation with a speech therapist and ask the patient to begin exercises before treatment. Working with a physical therapist before radiation therapy can help reduce loss of range of motion in the neck and shoulder.”

Speech-language pathologist Vanessa Sifontes, CCC-SLP, CMLDT, is also in clinic with the physicians to help screen patients and connect them with prehabilitation programs at TIRR Memorial Hermann Outpatient Rehabilitation locations in southwest Houston, Memorial City, the Greater Heights area, Katy, and at the Texas Medical Center. “The goal of prehabilitation is to prevent or lessen the severity of anticipated treatment-related problems that could lead to later disability,” Sifontes says. “Survivorship is difficult to quantify because each patient has a unique story, but we do know that patients who start early and are compliant with their exercise programs have fewer deficits after treatment.”

In addition to pre-surgical lymphedema evaluation, TIRR Memorial Hermann provides complete decongestive therapy for lymphedema patients, including manual lymphatic drainage, skin care, compression bandaging, therapeutic exercises, self-care training and patient and family education.

“This is a first-of-its-kind program,” Dr. Karni says. “The research we’re doing is having a direct impact on patient lives by providing their therapists with specific, individualized information. Normally it takes decades before work done in a lab is translated to patient care.”

After watching many people come in alone for chemotherapy, Kelly Jones has volunteered to provide support to other patients going through the experience. Looking back, he describes it as an incredible journey.

“Up until the age of 43, I had zero to complain about, then overnight my life changed,” he says. “Now I eat healthy, drink a lot of water and work out every day. I’m one of the lucky ones. My wife and I, we’ve been married for 30 years and she was there to help me. I’m back to racing motocross because I’m going to have fun. We’re living in a different world now. Cancer is everywhere. A lot of people don’t get a second chance like I did. I’m very blessed. Good things can come out of cancer.”