Gimme the Ear Tubes

In trying to sort out what to do with this blog and how it could be useful, I asked around among my friends what sort of topics could be useful.

“TUBES!!!” shouted the horde of crying, exhausted mothers.

“OK, I guess we can talk about those. What else?” I asked.

“TUBES!!!” they shouted again, even louder, and they threw their chai teas against the wall in what I can only guess is a cry for help.

“Ok, noted, but I guess—“

“TUBES!!!” they shouted. They followed me out to my car and rocked it back and forth as I started my car. A few of them were trying to stick their babies in my car as I rode away, and I had to lock my doors. The sound of thrown pacifiers clicking against my back window continued much longer than it should have. I’m pretty sure some of them were running after me.

So let’s talk about “tubes.” The full name is “Pressure Equalization Tube” (PET), and it’s one of the most common procedures that ENTs do. What are they? When do you need one? What can they do for you? Can you put them in right now? These are all the most common questions we get.

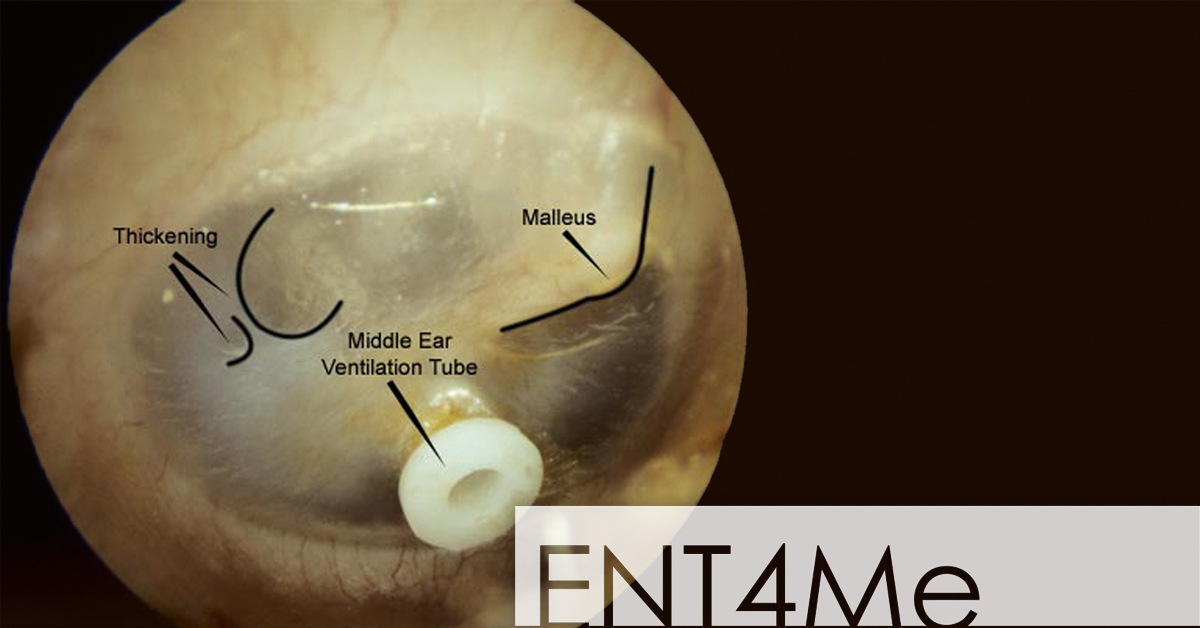

A PET is basically a pipe that gets inserted across the ear drum. Most of them look like the kind of pipes that Mario sinks through to get his coins; these are called Paparellas, an appropriately Italian name. Another is called a “Goode T-tube” which we pronounce “goodie,” as in, “Oh goodie, the last patient of the day wants me to put a T-tube in right now.” The Paparellas are supposed to last about 9 months to a year, and the T-tubes can last 1-2 years. These tubes help drain fluid from the middle ear into the external ear canal, and this helps relieve pressure, prevent severe infections, and sometimes improve hearing.

You need an ear tube when you have chronic otitis media, which are fancy words for fluid behind the ear drum on either a prolonged or recurrent basis. Kids and adults have different reasons for getting ear tubes. In kids, we usually check an audiogram or hearing test to see if there is fluid behind the ear drum and if there is a “conductive hearing loss” (CHL). Conductive hearing loss means that sound energy is not being properly transferred into the inner ear, decreasing hearing. In this case, if there is CHL and there is fluid behind the ear drum, then the decision is easy. We go ahead and put the ear tubes in with kids, because we want to preserve their hearing while they are developing language. In adults though, it’s left up to a discussion between the ENT and the patient. Most of the time, I will encourage adults to try to gently “pop your ears” like you would on an airplane and try various decongestants to attempt to resolve the otitis media without making a hole in the eardrum.

Notice I didn’t say anything about a number of infections, which often blows people’s minds these days. The reason is that our academy mainly points to CHL as a firm indication for ear tubes. The frequency of ear infections as an indication is left up to the discretion of the ENT, since there’s no “magic number” of ear infections that triggers a significant increase in risk for the patient. The recommendation from the academy is to avoid ear tubes if there is no fluid behind the ear drum at the time of evaluation, because we’re trying to prevent risks of anesthesia exposure and surgery in kids.

In adults, we can put the ear tubes right in through the ear canal in the office. In kids though, usually we have to do a little sedation in the OR, since kids get wiggly and hard to hit with a tranquilizer dart. It takes a little less than 30 minutes. If awake, there is a little bit of burning from the ear drum when we put the numbing medicine on, but after that it’s pretty tolerable as long as you can sit still. There’s not much risk, though holes in the eardrum are a bit difficult to predict. The vast majority close on their own, but there are some that stay open and require other procedures to close them.

So those are ear tubes. *Cue noise of Mario sinking into a pipe*