Preventing Surgical Fires: UTHealth Otolaryngologist Provides Expert Advice for a New FDA Safety Initiative

A longstanding interest in improving operating room safety has led to the appointment of pediatric otolaryngologist Soham Roy, MD, FACS, FAAP, as a medical consultant for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Preventing Surgical Fires initiative. Dr. Roy is an associate professor of pediatric otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, director of pediatric otolaryngology and director of undergraduate medical education for otolaryngology at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) Medical School.

A longstanding interest in improving operating room safety has led to the appointment of pediatric otolaryngologist Soham Roy, MD, FACS, FAAP, as a medical consultant for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Preventing Surgical Fires initiative. Dr. Roy is an associate professor of pediatric otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, director of pediatric otolaryngology and director of undergraduate medical education for otolaryngology at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) Medical School.

An estimated 550 to 650 surgical fires occur in the United States each year, according to the FDA, some causing serious injury, disfigurement and, more rarely, death. This statistic prompted the FDA to partner with 24 public and private healthcare organizations with expertise in product use, risk management, standard setting and other areas related to quality care and safety on the Preventing Surgical Fires initiative, which falls under the agency’s overarching Safe Use Initiative.

Careful attention to the inherent risks of fire in the OR and a team approach are critical in preventing serious harm.

“Operating room fires are an unspoken hazard that pose a significant risk of harm to surgical patients, particularly in otolaryngology-head and neck surgical procedures,” says Dr. Roy, a nationally and internationally recognized expert on OR safety. “Procedures involving the face, head and neck pose the greatest danger for operating room fire due to the combination of exposed supplemental oxygen, flammable materials and ignition sources like cautery devices and lasers. The use of electrosurgical devices to open the trachea appears to pose a particularly high risk.”

In 2008, Dr. Roy and his research partner Lee P. Smith, MD, a former resident who trained with Dr. Roy at the University of Miami School of Medicine and is now an assistant professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, surveyed members of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery about their experience with surgical fires. A quarter of the respondents had witnessed a fire in the operating room, and the frequency of fires was comparable in several procedures, including endoscopic airway surgery, oropharyngeal surgery, cutaneous surgery and tracheostomy. Eighty-five percent of the fires occurred in the presence of oxygen (1). That same year, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) issued a practice advisory about the prevention and management of operating room fires.

“As with any potential hazard, awareness is the first step in prevention,” Dr. Roy says. “The ASA detailed several precautions for OR teams to follow to help avoid surgical fires.”

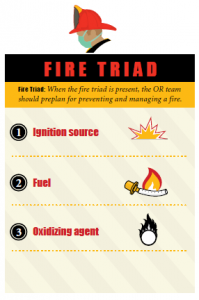

Before each surgical case, the OR team should determine if the case is at high risk for a surgical fire. If the “fire triad” is present – an ignition source, fuel such as endotracheal tubes and operating room drapes, and an oxidizing agent—the team should pre-plan for preventing and managing a fire.

Before each surgical case, the OR team should determine if the case is at high risk for a surgical fire. If the “fire triad” is present – an ignition source, fuel such as endotracheal tubes and operating room drapes, and an oxidizing agent—the team should pre-plan for preventing and managing a fire.

Careful attention to the inherent risks of fire in the OR and a calculated team approach between OR nurses, surgical technologists, surgeons and anesthesia providers is critical in preventing serious harm, says Dr. Roy, who has lectured and published widely on the risk of fire in the OR. “The anesthesiologist should collaborate with all surgical team members throughout the procedure to minimize the presence of an oxidizer-enriched atmosphere in proximity to an ignition source. One of our studies evaluating the minimum oxygen requirements to obtain a fire in our mechanical model suggests that a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) below 50 percent may eliminate the risk of fire ignition(2). We have performed additional studies to quantify these risks.”

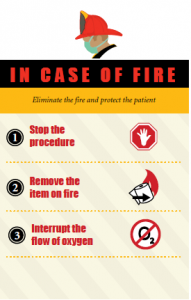

Medical professionals agree that the most important action to take in the case of surgical fire is to eliminate the fire and protect the patient. As early as 2003, the Joint Commission issued a sentinel event alert on reducing surgical fires. In the alert, the group recommends that healthcare organizations help prevent surgical fires by informing staff members of the importance of controlling heat sources through safety practices, managing fuels by allowing sufficient time for patient prep to evaporate, establishing guidelines for minimizing oxygen concentration under the drapes, and developing and implementing procedures to ensure appropriate response by all members of the surgical team to fires in the OR.

Medical professionals agree that the most important action to take in the case of surgical fire is to eliminate the fire and protect the patient. As early as 2003, the Joint Commission issued a sentinel event alert on reducing surgical fires. In the alert, the group recommends that healthcare organizations help prevent surgical fires by informing staff members of the importance of controlling heat sources through safety practices, managing fuels by allowing sufficient time for patient prep to evaporate, establishing guidelines for minimizing oxygen concentration under the drapes, and developing and implementing procedures to ensure appropriate response by all members of the surgical team to fires in the OR.

“The staff should act quickly and calmly to extinguish the fire and protect the patient from injury,” he says. “Three steps should be taken immediately and simultaneously: stop the procedure, remove the item on fire and interrupt the flow of oxygen.”

In his new role with the FDA, Dr. Roy will help identify barriers to safe practices with the ultimate goal of engaging all hospitals in developing specific, tangible interventions to reduce surgical fires. “We estimate that as many as 1,000 events may go unreported each year,” he says. “As part of the Preventing Surgical Fires initiative, we’d like to reduce that number to zero. ‘One is too many’ is our tagline for the initiative.”

Dr. Roy strongly encourages organizations to report surgical fires as a means of raising awareness and ultimately preventing future fires. Reports can be made to the Joint Commission, the ECRI Institute, the FDA and state agencies, among other organizations. “While airway fires are a significant risk in the OR, through awareness, use of the proper tools and preventive measures, we can easily avoid them.”

References

- Smith LP, Roy S. Operating room fires in otolaryngology: Risk factors and prevention. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 2011. Mar-Apr;32(2):109-14.

- Roy S, Smith LP. What does it take to start an oropharyngeal fire?: Oxygen requirements to start fires in the operating room. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 2011. Feb;75(2):227-30.