Modern History of Aortic Surgery, by Hazim J. Safi, MD

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”—Sir Isaac Newton said 1642-1727.

While the history of aortic surgery dates back to Greek surgeon Antyllus, who first performed surgeries for various aneurysms in the second century AD, the majority of advancements has been in the past century and, primarily, from the Houston, Texas, group led by Dr. Michael DeBakey.

Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1908, DeBakey attended Tulane University in New Orleans, where he met Drs. Alton Ochsner and Rudolph Matas, two of the true giants in vascular surgery. DeBakey furthered his education in aortic surgery in the 1930s, visiting Europe and training in Strasbourg, France, before returning to New Orleans. During this time, he contributed tremendously to the art of blood transfusion, inventing the roller pump, which was subsequently incorporated into Dr. John Gibbon’s heart-lung bypass machine.

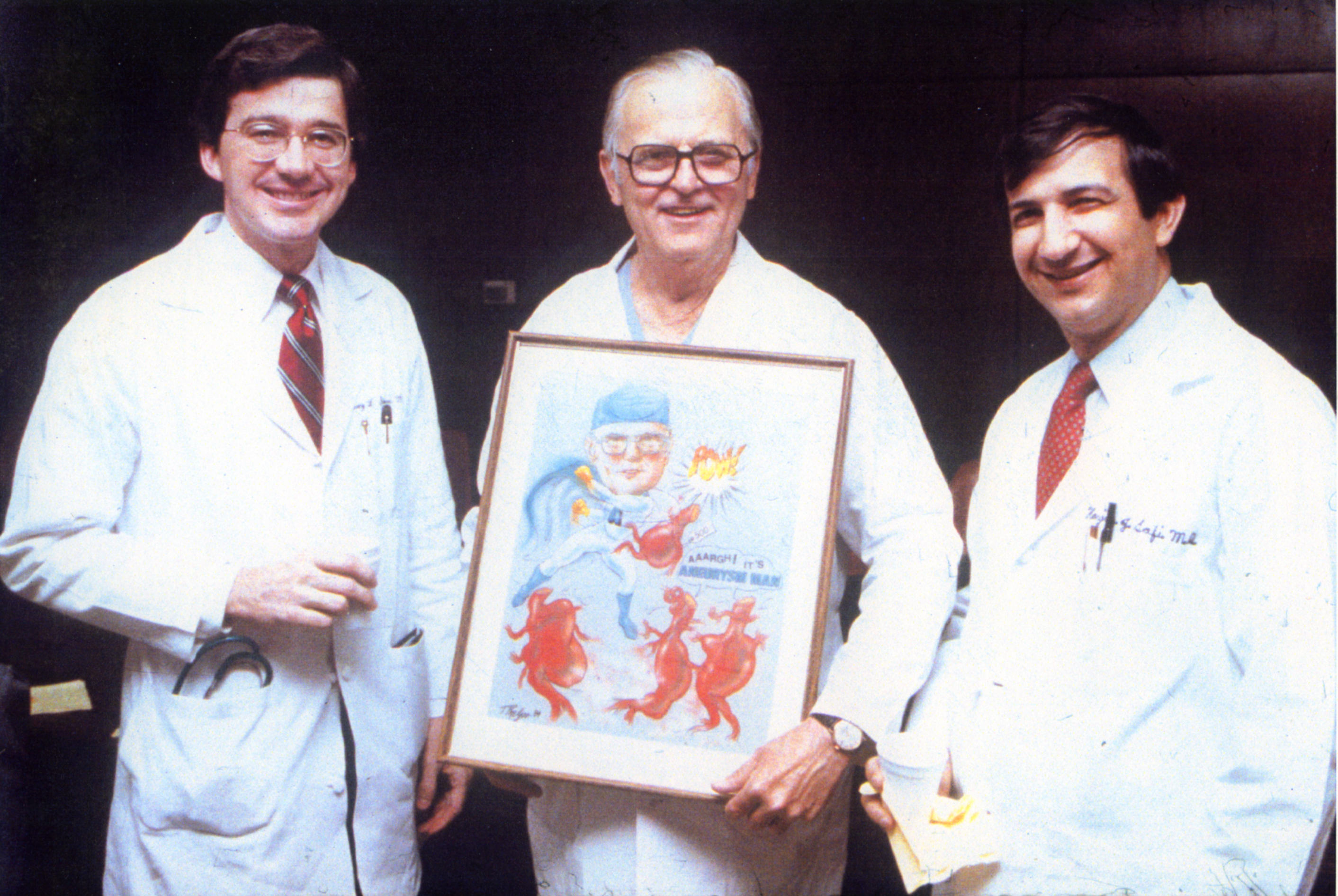

Left to right, Drs. Cary Stowe, E. Stanley Crawford, and Hazim Safi

In the 1940s, the Baylor College of Medicine moved from Dallas to Houston. After protracted discussions, in 1948, Baylor named DeBakey its chair for the Department of Surgery. He immediately surrounded himself with a brilliant team of surgeons, including Drs. Denton Cooley and E. Stanley Crawford. Together, they began tackling various aortic aneurysms one case at a time.

In 1955, DeBakey and Cooley performed the first replacement of a thoracic aneurysm with a homograft. In 1958, they began using the Dacron graft, resulting in a revolution for surgeons in the repair of aortic aneurysms. He also was first to perform cardiopulmonary bypass to repair the ascending aorta, using antegrade perfusion of the brachiocephalic artery. These were all major breakthroughs.

Around this time, the group made one of the biggest contributions to the field by establishing three categories of acute aortic dissections. Called DeBakey classifications, they include: Type I, involving the ascending and descending aorta; Type II, the ascending aorta only; and Type III, the descending aorta only, commencing after the origin of the left subclavian artery. Amazingly, we still use these classifications today.

By the mid-1960s, DeBakey’s group began tackling thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm (TAAA), which presented formidable surgical challenges, often fraught with serious complications, such as paraplegia, paraparesis and renal failure. Crawford, in particular, began dedicating most of his time to TAAAs. It took him 10 years to accrue 22 cases. However, over the next 10 years, they accumulated more than 500 TAAA cases. He classified these cases into four types: Extent I, extending from the left subclavian artery to just below the renal artery; Extent II, from the left subclavian to below the renal artery; Extent III, from the sixth intercostal space to below the renal artery; and Extent IV, from the twelfth intercostal space to the iliac bifurcation (i.e. total abdominal). For the first time, this created a meaningful look into these difficult conditions. In 1992, we added another classification, Extent V, characterized by aneurysmal disease extending from the sixth intercostal space to above the renal arteries.

Around this time, we revisited the problem of neurological deficit (spinal cord ischemia). We used experimental animal models for a prospective study on the use distal aortic perfusion, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, moderate hypothermia and sequential clamping to decrease in the incidence of neurological deficit. In 1994, we presented our experience at the Southern Association for Vascular Surgery, showing that the incidence for Extent I and II dropped from 25% to 5%. This marked a new era for protecting the spinal cord, brain, kidneys, heart and lungs.

Current results are even better. Today, spinal cord ischemia after the repair of thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms is: Extent I, less than 2%; Extent II, less than 4% (previously 31%); Extent III, less than 2%; Extent IV, less than 2%; Extent V, less than 1%. This shows the tremendous positive impact these techniques have made with regard to spinal cord protection.

In September 1999, I moved from Baylor to the University of Texas Medical School at Houston to establish the Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery. The department has grown from the initial 2 surgeons to more than 20. We have a program in cardiac surgery, vascular surgery, thoracic surgery and a renowned research department. The department is well-known both nationally and internationally. In fact, our team members have demonstrated our techniques on six of the seven continents (all but Antarctica). In regard to academic output, the department publishes nearly 50 papers and abstracts per year. We also have an advanced aortic fellowship from 1 to 2 years.

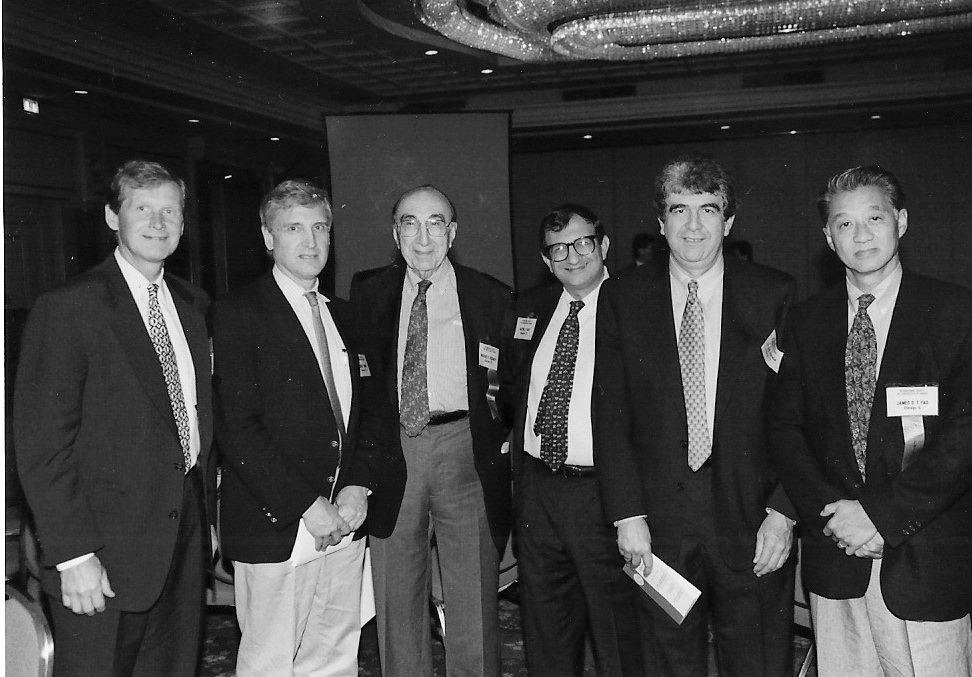

Hazim Safi, MD with several members of the UTHealth cardio, thoracic, and vascular surgery residency and fellowship programs

In 2019, after 20 years at the helm, I stepped aside as leader of the department. The new chair is Anthony Estrera, MD. Under his leadership, the future will be very bright for at least another two decades, continuing the legacy of DeBakey, Cooley and Crawford.

By Hazim J. Safi, MD

Hazim Safi, MD is founding chair and professor of the cardiothoracic & vascular surgery department at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth. In March of 2020, Dr. Hazim Safi was presented with a Festschrift at McGovern Medical School, to commemorate and pay tribute to his advancements as a physician, contributions as an academic, and commitment to his family, co-workers, and patients. Dr. Safi still works with the residents and fellows at UTHealth, and continues to operate at Memorial Hermann Heart & Vascular Institute.