Developing Better Laboratory Models of Neonatal Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Hydrocephalus

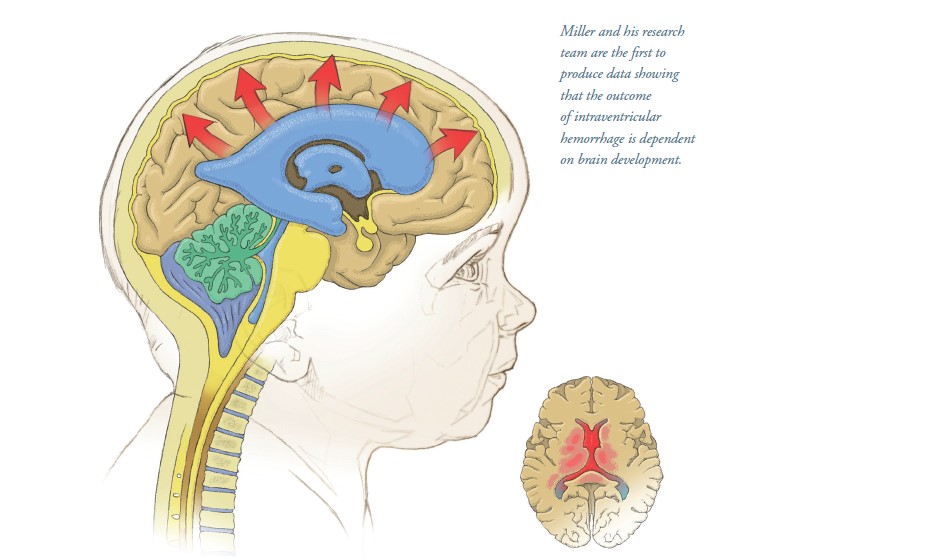

Among the most common conditions treated by pediatric neurosurgeons are neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) and posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. While neonatal IVH has been studied in various laboratory models, the effects of brain development on IVH and hydrocephalus have not been assessed. In a paper published in Experimental Neurology,1 Brandon A. Miller, MD, PhD, FAANS, and his laboratory team at UTHealth Houston have shown in a laboratory model how brain development determines the extent of inflammation and eventual outcome of IVH.

The research is funded by Miller’s National Institutes of Health K08 Clinical Investigator Award focused on reversing inflammation as treatment for IVH. “Neonatal IVH is a common complication of premature birth, and it occurs at a time when both the brain and immune system are developing,” says Miller, an assistant professor in the Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery at McGovern Medical

School at UTHealth Houston. “We use laboratory models to study how IVH affects the brain at different stages of development and how different therapies can reduce inflammation after IVH and prevent hydrocephalus.”

Neonates who suffer IVH are at risk for sudden and potentially fatal hydrocephalus. Working with an animal model, Miller and Miriam Zamorano, PhD, a research scientist in the Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery at the medical school, noted on imaging studies that hydrocephalus did not develop immediately after IVH. “Looking at ultrasound images of the brains of infants with IVH and hydrocephalus inspired us to refine our work in the laboratory,” says Zamorano, who joined Miller’s lab in September 2021, attracted by the opportunity to work with an MD/PhD and move her work from basic science to clinical trials. “We wanted to better simulate the human disease in the laboratory, and develop a model that mimicked what was occurring in the brains of patients with IVH and hydrocephalus.

This led us to modify our experimental procedures and led to the important discovery that as the brain and immune system ages, the response to IVH became worse – with more inflammation and worse hydrocephalus.” Zamorano tested the effects of IVH at two different developmental time points meant to simulate different stages of brain development in preterm infants.

“We wanted to study the response to IVH in a narrow and developmentally important age range,” Miller says. “We initially thought that the effects of IVH would be most severe in the most immature brain, but this was not the case. Instead, we found that the effects of IVH began to manifest in later stages of brain development. Our data is the first to show that the outcome of IVH is dependent on brain development, suggesting that post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus depends on inflammation that occurs as the brain develops.

“One of the reasons I came to UTHealth Houston is the atmosphere of collaboration between clinicians and scientists,” Miller adds. “We have collaborative teams of PhDs and MDs working together toward the same goal, and this paper is evidence of that. What we’re doing in our model is a snapshot of what happens in humans. We’ve combined laboratory and human data in this new publication and are using the laboratory model to test drugs and stem cell therapies that we can use in humans. Our goal is to help kids have better outcomes and lead better lives, and each step we take to move our work in the lab to clinical trials brings us a little closer.”

1Zamorano M, Olson SD, Haase C, Herrera JJ, Huang S, Sequeira

DJ, Cox Jr CS, Miller BA. Innate immune activation and white matter injury in a rat model of neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage are dependent on developmental stage. Exp Neurol. 2023 Sep;367;114471. Epub 2023 Jun 17.

Inside this Edition:

- Responsive Neurostimulation for Generalized Epilepsy in an 18-Year-Old

- The NICU Follow-Up Clinic: Everything Premature Babies Need To Get the Best Start in Life

- Team-Based Medicine Leads to Nonsurgical Repair of Depressed Skull Fractures in Two Neonates

- Watchful Waiting for Cerebral Venous Thrombosis Allows a Boy To Avoid Brain Surgery

- UTHealth Houston Team Completes Feasibility Study for Minimally Invasive Myelomeningocele Repair in 25 Patients

- Developing Better Laboratory Models of Neonatal Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Hydrocephalus

- Researchers Seek to Improve Outcomes in Children with Malignant Fourth Ventricular Brain Tumors Through Novel Studies

- McGovern Medical School Alumni Blend Neurology Expertise and Philanthropy To Advance Pediatric Tumor Research