Responsive Neurostimulation for Generalized Epilepsy in an 18-Year-Old

Lynn Townes had just moved her family into a new home and lay down to rest, when she heard her son scream. She jumped up, ran to the dining room, and found her 10-year-old daughter Savannah Nguyen convulsing on the floor.

“At first I thought she was choking, but the kids had been playing a board game, not eating. My son’s girlfriend had seen Savannah’s eyes roll back and caught her as she fell to the floor,” Townes recalls. “We called 911 and when we arrived at the hospital she looked at us like ‘What happened?’ – completely unaware that she had had a seizure.”

That was the first of many uncontrolled tonic clonic seizures Nguyen would suffer over the next seven years. During puberty, her seizures worsened. “Savannah had an intense seizure almost every two weeks with periods of absence in between,” Townes says. “She was a competitive figure skater – we traveled around the country to

competitions – but she started having absence seizures on the ice and her coach would catch her before she fell. So we had to give that up.”

After her daughter trialed and failed numerous anticonvulsive medications over a four-year period, Townes learned about Gretchen Von Allmen, MD, and made an appointment in October 2019 for a second opinion. Von Allmen is professor of pediatrics and the Jacobo Geissler Distinguished Chair in West Syndrome Research, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Program, and director of the Division of Child and Adolescent Neurology at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston.

After her daughter trialed and failed numerous anticonvulsive medications over a four-year period, Townes learned about Gretchen Von Allmen, MD, and made an appointment in October 2019 for a second opinion. Von Allmen is professor of pediatrics and the Jacobo Geissler Distinguished Chair in West Syndrome Research, director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Program, and director of the Division of Child and Adolescent Neurology at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston.

“Savannah was taking two medications that were not controlling her seizures,” Von Allmen says. “She had never had an MRI or EEG, and no treatments were suggested beyond medications that weren’t working. After a child fails two or more appropriate medications, we diagnose intractable epilepsy and look for non-medication treatment options.”

In December 2019, Nguyen was admitted to the Epilepsy Monitoring Unit for a Phase 1 presurgical evaluation, which included high-resolution MRI to visualize brain structure, scalp video-EEG monitoring to capture and characterize the seizures and possibly pinpoint the region where seizures begin, and a detailed neuropsychological assessment.

Von Allmen also ordered a magnetoencephalography (MEG) study, which evaluates epilepsy and brain function noninvasively, measuring small electrical currents inside the brain’s neurons that produce magnetic fields. When evaluated in combination with the results of an MRI, MEG can complement the EEG findings to more accurately identify brain areas that generate seizures, as well as identify important functional areas of the brain that should not be disturbed with surgery.

“The presurgical evaluation showed that her seizures were multifocal with a focal initiation on the left side, so we scheduled her for stereoencephalography (SEEG) to see if we could identify a focal area for resection,” Von Allmen says. SEEG is a minimally invasive surgical procedure to locate precisely the areas of the brain from which seizures originate.

Prior to the SEEG procedure in June 2020, Von Allmen changed Nguyen’s medications to determine whether others might produce a better result, although once a patient has failed two or more anticonvulsant medications, the chances of a response with medications alone is less than 5%.

Manish N. Shah, MD, FAANS, associate professor of pediatric neurosurgery and the William J. Devane Distinguished Professor at McGovern Medical School, placed electrodes in the targeted areas of Nguyen’s brain agreed upon by the epilepsy program team to allow for monitoring that they hoped would find the precise source of her seizures. But the study showed that her epilepsy is generalized, with seizures that can occur anywhere in the brain without apparent cause. Surgery is not an option for these patients.

As an alternative, Nguyen’s epilepsy team suggested vagus nerve stimulation, also known as VNS Therapy®. VNS is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an addon therapy for adults and children four years and older to treat focal or partial seizures that do not respond to medication. The device, implanted under the skin in the left chest area, includes a wire that the surgeon winds around the vagus nerve in the neck. The device is programmed to deliver pulses or stimulation to the nerve at regular intervals to prevent seizures or arrest them as they start.

Shah implanted the VNS in June 2019. “It appeared that Savannah had some initial improvement, but with VNS we always give it some time to work while we watch closely,” Von Allmen says. “In the end the VNS reduced the length of her seizures, but they continued to occur. After much discussion with the family, we decided to try responsive neurostimulation of the thalamus using the NeuroPace RNS® System.”

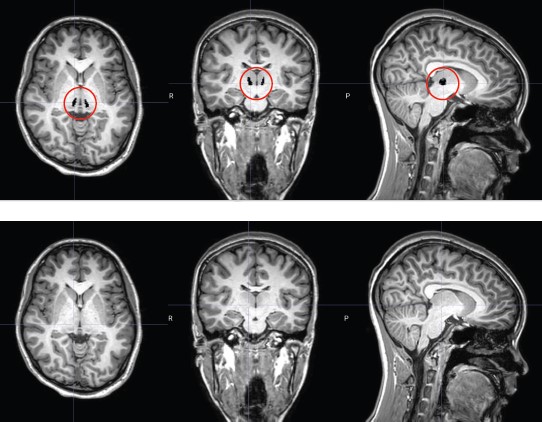

RNS electrode placement in a tiny spot of the thalamus called the centromedian nucleus requires expertise and microscopic precision.

Responsive neurostimulation monitors brain waves at the seizure focus 24/7 and detects any unusual electrical activity that may lead to a seizure. It also responds quickly to activity that appears to be a seizure, delivering small pulses of stimulation. The RNS System has been approved by the FDA to treat focal or partial seizures in adults 18 years and older and is used in addition to anticonvulsive medications. Although RNS is not a cure for epilepsy, it has been shown to reduce seizure activity in most people.

Nguyen celebrated her 18th birthday in September 2022, and Shah implanted the RNS in her skull on Dec. 20, placing its tiny leads deep into the thalamus in a minute spot called the centromedian nucleus. “This is a very difficult spot to target,” he says. “It’s only a few millimeters in size and the electrodes have to sit perfectly within it. If they are even slightly off position, the patient can experience significant pain. We placed electrodes in both the left and right sides of the centromedian nucleus and attached them to the RNS.”

Once implanted, the RNS is programmed to recognize each patient’s unique seizure patterns, responding with stimulation to prevent seizures before they start. It also records and reports EEG data to help doctors understand more about the seizures and personalize stimulation.

“We work closely with Dr. Sandipan Pati, an adult epileptologist who helps us program the devices and is a real strength of our program,” Von Allmen says. “Thanks to our pediatric epilepsy program’s close collaboration with UTHealth Houston’s adult epileptology program, we can provide continuity of care for patients with difficult-to-manage seizures as they grow to adulthood. This is especially important for teenagers like Savannah who will transition to adult epilepsy care.”

An associate professor of neurology, Pati has clinical and research interests focused on treatment-resistant epilepsies, with the goal of developing efficient neuromodulation paradigms to treat seizures and cognitive comorbidities, such as depression and memory loss. “Our goal is to minimize seizures and space them as far apart as possible,” he says. “The device changes the epileptic networks over time, so patients come to me periodically to reprogram the device. It can take up to six months to program an RNS device to meet an individual’s specific needs and as long as two years to get full benefit in terms of seizure reduction. The frequency and severity of Savannah’s seizures have decreased significantly in a few months.”

The RNS System has also been shown in a nine-year study to significantly lower the rate of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP).1 Most, but not all cases of SUDEP occur during or immediately after a seizure, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pati sees patients 18 years of age and older but collaborates with the pediatric epilepsy team when they feel the RNS is the best option for patients between 12 and 18 years of age. “While RNS is FDA approved for people with intractable epilepsy age 18 or older, epileptologists may use it off-label for children younger than 18 when there is no other solution,” he says. “We always try medication first. If they have generalized tonicclinic seizures and fail two or more medications, they are at risk for SUDEP. Our No. 1 goal is to stop the seizures and our No. 2 goal is to make sure the RNS system is programmed to quickly terminate any seizure that starts. In many patients it works well, and they benefit enormously.”

Nguyen’s RNS was implanted five days before Christmas in 2022. “We had a full house on Christmas Eve, and she was a happy child, playing like normal,” her mother says. “They programmed the device on Jan. 9, 2023, and started stimulation two days later. The stimulation didn’t bother her, but she was still having seizures every two weeks, so Dr. Pati increased the level last March, which also didn’t bother her. She went almost five weeks before having a seizure, then went almost three weeks before another one. So hopefully, with continued adjustment, we can go longer. On the

positive side, she’s much better than before we made the decision to have the RNS implanted.”

“By decreasing her seizure burden more than 60%, we’re also decreasing her SUDEP mortality risk,” Pati says.

Nguyen will continue to be monitored by her team of doctors, and after graduation from high school in May 2023, she is considering college. “We’re taking baby steps and plan to do one class in school and one class online to get started,” Townes says. “I’m nervous about her going to school but I know I can’t keep her home all the time. After all her exposure to the medical world, she’s interested in doing something in medicine.

“We’re just continuing on and praying for the best,” she adds. “Hopefully, this will be our cure. Savannah has always been a happy child and now she’s so much better. This has become normal for us. She’s living with epilepsy but she’s not going to let it control her life. And we’re here to provide support and take care of her.”

1Nair DR, Laxer KD, Weber PB, et al. Nine-year prospective efficacy and safety of brain-responsive neurostimulation in focal epilepsy. Neurology. 2020 Sept 1:95(9).

Inside this Edition:

- Responsive Neurostimulation for Generalized Epilepsy in an 18-Year-Old

- The NICU Follow-Up Clinic: Everything Premature Babies Need To Get the Best Start in Life

- Team-Based Medicine Leads to Nonsurgical Repair of Depressed Skull Fractures in Two Neonates

- Watchful Waiting for Cerebral Venous Thrombosis Allows a Boy To Avoid Brain Surgery

- UTHealth Houston Team Completes Feasibility Study for Minimally Invasive Myelomeningocele Repair in 25 Patients

- Developing Better Laboratory Models of Neonatal Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Hydrocephalus

- Researchers Seek to Improve Outcomes in Children with Malignant Fourth Ventricular Brain Tumors Through Novel Studies

- McGovern Medical School Alumni Blend Neurology Expertise and Philanthropy To Advance Pediatric Tumor Research