ORL’s 360 Research Program Translates New Laboratory Discoveries to Patient Care

Since her 2008 arrival at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center and the McGovern Medical School, Amber Luong, MD, PhD, FACS, has focused much of her attention on building a translational otorhinolaryngology research program from the ground up. Today, those efforts are paying off in better outcomes for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), as physicians in the department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery quickly move novel treatments from the laboratory to direct patient care through clinical trials.

Amber Luong, MD, PhD

“We don’t fully understand the disease process of chronic rhinosinusitis, a condition diagnosed in more than 30 million Americans annually,” says Dr. Luong, an associate professor and research director in the department of Otorhinolaryngology who also directs a laboratory at the Brown Foundation Institute of Molecular Medicine for the Prevention of Human Diseases. “The disease accounts for about $6 billion annually in treatment costs, making it one of the most costly non-fatal diseases to manage. We have knowledge of some of the potential triggers for CRS – viruses, bacteria and fungal exposure – but we aren’t certain which of the triggers affects individual patients. Our research goal is to develop directed curative treatment options for CRS through a better understanding of the triggers and molecular mechanisms that are important in the disease process. Learning more about CRS will give us a better idea of how to treat the cause of the disorder rather than just the symptoms, which is the focus of most current treatment. We’re not stopping with basic science. We’re taking our laboratory discoveries all the way through to patient care.”

The department’s robust translational research program stems from Dr. Luong’s training in the National Institutes of Health-sponsored Medical Scientist Training Program at UT Southwestern Medical Center, where she received her MD/PhD Two Nobel laureates, Michael S. Brown, MD, and Joseph L. Goldstein, MD, served as mentors for her PhD work during the eight-year program.

“They were great role models,” Dr. Luong says. “Here were two physicians who evolved from caring for individual patients to conducting research to acquire new knowledge that will help hundreds of patients. For the first time I understood the possibility of a medical career that combines clinical medicine and basic science research in a distinctive way. As a physician-scientist you can learn about the disease process as it manifests in patients, each of whom is very different, and use the knowledge and experience of treating patients to frame research questions and interpret the results in the lab, and vice versa. Information I gain as a scientist makes me think about the applicability to treatment or the understanding of human diseases. By bringing together these two worlds, translational medicine is born.”

Her desire to meld basic science with clinical treatment has led to the publication of several groundbreaking studies focused on understanding the pathophysiology of allergic fungal rhinosinusitis as a model for studying immune dysregulation of the paranasal sinuses; IL-33 as a pathway in chronic rhinosinusitis; the role of intranasal capsaicin as a diagnostic tool and a treatment for non-allergic irritant rhinitis; and molecular pathways by which fungus can stimulate chronic rhinosinusitis. One study, conducted by researchers at the McGovern Medical School and Baylor College of Medicine, demonstrated for the first time the functional importance of innate lymphoid cells in type 2-mediated inflammatory disease in humans (1).

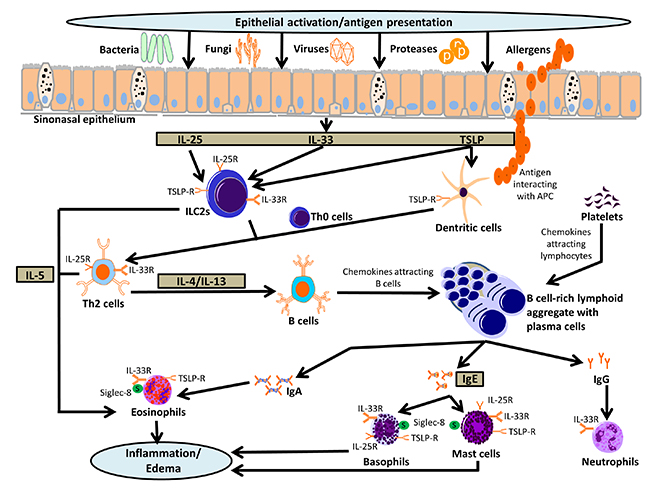

Schematic of molecular pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis.

This pictorial highlights the role of the epithelial cell barrier and epithelial cell derived cytokines, IL-25, IL-33 and TSLP, as orchestrators of the innate and adaptive immune response leading to chronic sinonasal inflammation.

“The aim of the study was to investigate the role of the epithelial cell-derived cytokine interleukin-33 (IL-33) and IL-33-responsive innate lymphoid cells in the pathophysiology of chronic rhinosinusitis,” Dr. Luong says. “From previous studies in an animal model we knew that IL-33 plays a key role in the development and regulation of a type 2 immune response, mediated by an IL-33-responsive innate lymphoid cell population, but until now there was little direct evidence of an important role for these cells in type 2-mediated inflammatory disease in humans. We were able to show that the percentage of innate lymphoid cells is significantly elevated in diseased mucosa in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps – a type 2-mediated inflammatory process – and that these cells represent a consistent and potentially important source of IL-13 in response to IL-33 stimulation.”

Dr. Luong’s study is one of a handful to identify a human disease in which the IL-33 pathway is important. Currently, she and other rhinologists in the department are actively recruiting participants for a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial examining ways to block the IL-33 molecule for management of CRS with nasal polyps.

In the same study, the researchers also found that epithelial cells release IL-33 upon challenge with fungus. Later, Dr. Luong was a collaborator in a related study at Baylor College of Medicine, the results of which were published in Science in 2013 (2). Led by David Corry, MD, a professor in the departments of Pathology & Immunology and Medicine-Pulmonary and Critical Care at Baylor, the research team described how fungus signals through epithelial and immune cells to trigger a type 2 inflammatory response leading to airway hypersensitivity.

Through their protease activity, fungus cleaves fibrinogen-releasing degradation products that bind and activate toll-like receptor 4. The researchers found that toll-like receptor 4 does not directly activate T cells but instead leads to the expression of the IL-13 receptor, causing the typical symptoms of asthma and suggesting a connection between fungal infections and asthma. In another collaborative study with Dr. Corry, Dr. Luong showed that fungal load is elevated within diseased sinus cavities but also can be found in non-diseased cavities. However, only immune memory to fungal species specifically found within diseased sinus cavities were evident in patients with CRS and not in healthy controls, linking an active role of fungi in the pathophysiology of some CRS patients (3). Today, a clinical trial under way at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center is investigating the addition of antifungal agents to typical post-operative treatment to treat CRS patients with fungal sensitivity.

“Because our basic science work demonstrated that fungus stimulates an immune response seen in chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma, it made sense to us that an antifungal agent would help by eradicating the thing that’s driving the immune response,” she says. “That’s one more example our 360 direction, translating basic science quickly to patient care.”

Dr. Luong and her research team are also investigating the use of intranasal capsaicin as a diagnostic tool and as a treatment for nonallergic irritant rhinitis (NAIR). Patients with NAIR have symptoms of nasal congestion, nasal irritation, rhinorrhea and sneezing in response to nasal irritants. Until recently, physicians had no reliable objective means of making the diagnosis of NAIR; it was a diagnosis of exclusion. Using capsaicin as an intranasal challenge, they compared changes in blood flow with optical rhinometry between subjects with NAIR and healthy controls. In addition, studies have suggested that multiple intranasal exposure to high dose capsaicin can serve as a treatment for NAIR(4).

“Study participants with NAIR showed a significant increase in blood flow relative to patients who don’t have this diagnosis,” she says. “Today, we’re continuing the development of this diagnostic tool and conducting a randomized blinded clinical trial in which we’re objectively identifying patients with NAIR and then randomizing patients to treatment with a high dose of capsaicin administered in five doses a day, each given one hour apart, or to placebo. We’re evaluating them at one month and three months to determine if the diagnostic response to capsaicin disappears, suggesting a positive treatment for NAIR.

“Laboratory breakthroughs like these mean that ultimately we’ll be able to help many more patients,” she adds. “It’s very rewarding to successfully treat one patient, but it’s also great to be able to help many patients through research. Our translational research program is a grand project: we’re looking for a cure for chronic sinus disease. Our long-term goal is to put ourselves out of business.”

References

- Shaw JL, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Porter PC, Corry DB, Kheradmand F, Liu Y-J, Luong A. IL-33-responsive Innate Lymphoid Cells Are an Important Source of IL-13 in Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013 Aug 15:188(4):432-9.

- Millien VO, Lu W, Shaw J, Xuan X, Mak G, Roberts L, Song L-Z, Knight JM, Creighton CJ, Luong A, Kheradmand F, Corry DB. Cleavage of Fibrinogen by Proteinases Elicits Allergic Responses Through Toll-Like Receptor 4. Science. 2013 Aug 16;341(6147):792-6.

- Porter PC, Lim DJ, Maskatia ZK, Mak G, Tsai CL, Citardi MJ, Fakhri S, Shaw JL, Fothergil A, Kheradmand F, Corry DB, Luong A. Airway surface mycosis in chronic TH2-associated airway disease. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014 Aug;134(2):325-31.

- Lambert EM, Patel CB, Fakhri S, Citardi MJ, Luong A. Optical rhinometry in nonallergic irritant rhinitis: a capsaicin challenge study. International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology. 2013 Oct;3(10):795-800. [Epub 2013 Jun 3]